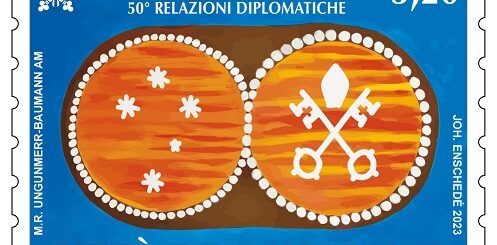

POSTE ITALIANE 21-22-23-24^ emissione del 20 luglio 2020 di un foglietto con n.4 francobolli dedicati a Raffaello Sanzio, nel V° centenario della scomparsa

POSTE ITALIANE 21-22-23-24^ emissione del 20 luglio 2020 di un foglietto con n.4 francobolli dedicati a Raffaello Sanzio, nel V° centenario della scomparsa

Il Ministero dello Sviluppo Economico con le Poste Italiane emette il 20 luglio 2020 francobolli ordinari appartenenti alla serie tematica “il Patrimonio artistico e culturale italiano” dedicati a Raffaello Sanzio, nel V centenario della scomparsa, relativi al valore della tariffa B zona 2 50 g, corrispondenti ognuno ad €.3.90.

Vignette: i quattro francobolli, racchiusi in un foglietto, riproducono rispettivamente un’opera di Raffaello Sanzio e precisamente, partendo dall’alto, da sinistra a destra:

- Autoritratto – Gallerie degli Uffizi, Firenze

- Trionfo di Galatea – Villa Farnesina, Roma

- Madonna col Bambino – Casa Natale di Raffaello, Urbino

- Sposalizio della Vergine – Pinacoteca di Brera, Milano.

- data 20 luglio 2020

- dentellatura 11

- stampa rotocalcografia

- tipo di carta carta bianca patinata neutra autoadesiva

- stampato I.P.Z.S. Roma

- tiratura foglietto 200.000

- dimensioni foglietto 185 x 130 mm

- valore B zona 2 50 g = €3.90 cadauno

- bozzettista: T. Trinca e a cura del Centro Filatelico della Direzione Operativa dell’Istituto Poligrafico e Zecca dello Stato S.p.A.

- num. catalogo foglietto Michel BL85 YT UN BF101

- num. catalogo Autoritratto Michel 4203 YT UN 4046

- num. catalogo Trionfo di Galatea Michel 4204 YT UN 4047

- num. catalogo Madonna col bambino Michel 4205 YT UN 4048

- num. catalogo Sposalizio della Vergine Michel 4206 YT UN 4049

Se sei interessato all’acquisto di questo foglietto lo puoi acquistare al prezzo di € 20.00. Inviami una richiesta alla email: protofilia1@gmail.com

Raffaello Sanzio (Urbino, 28 marzo o 6 aprile 1483 – Roma, 6 aprile 1520) è stato un pittore e architetto italiano, tra i più celebri del Rinascimento. Considerato uno dei più grandi artisti d’ogni tempo, la sua opera segnò un tracciato imprescindibile per tutti i pittori successivi e fu di vitale importanza per lo sviluppo del linguaggio artistico dei secoli a venire, dando vita tra l’altro a una scuola che fece arte “alla maniera” sua e che va sotto il nome di manierismo.

Biografia

Gioventù (1483-1504)

Origini (1483-1493)

Raffaello nasce a Urbino «l’anno 1483, in venerdì santo, alle tre di notte, da un tale Giovanni de’ Santi, pittore non meno eccellente, ma uomo di buono ingegno, e atto a indirizzare i figli per quella buona via, che a lui, per mala fortuna sua, non era stata mostrata nella sua bellissima gioventù. Raffaello fu il primo e unico figlio di Giovanni Santi e di Magia di Battista di Nicola Ciarla. Il cognome “Sanzio” infatti non è che una delle possibili declinazioni di “Santi”, in particolare derivata dal latino “Sancti” con cui Raffaello sarà poi solito, nella maturità, firmare le sue opere.

Prima formazione artistica

Nella formazione di Raffaello fu determinante il fatto di essere nato e di aver trascorso la giovinezza a Urbino, che in quel periodo era un centro artistico di primaria importanza che irradiava in Italia e in Europa gli ideali del Rinascimento. Raffaello apprese probabilmente i primi insegnamenti di disegno e pittura dal padre, che almeno dagli anni ottanta del Quattrocento era a capo di una fiorente bottega, impegnata nella creazione di opere per l’aristocrazia locale. Nella bottega del padre, il giovanissimo Raffaello apprese le nozioni di base delle tecniche artistiche, tra cui probabilmente anche la tecnica dell’affresco: una delle primissime opere a lui attribuite è infatti la Madonna di Casa Santi, delicata pittura murale nella casa familiare.

Primo incontro con il Perugino

Non è noto attraverso quali vie il giovanissimo urbinate arrivò a far parte della bottega del Perugino: non sembra infatti credibile la notizia del Vasari, secondo la quale Raffaello sia stato allievo del Perugino ancora prima della morte del padre e persino di quella della madre.

Apprendistato dal Perugino (1494-1498)

Le prime tracce della presenza di Raffaello accanto a Perugino sono legate ad alcuni lavori della sua bottega tra il 1497 e il nuovo secolo. In particolare si è ritenuto di vedere un intervento di Raffaello nella tavoletta della Natività della Madonna nella predella della Pala di Fano (1497) e in alcune figure degli affreschi del Collegio del Cambio a Perugia (dal 1498), soprattutto dove le masse di colore assumono quasi un valore plastico ed è accentuato il modo di delimitare le parti in luce e quelle in ombra, con un generale ispessimento dei contorni. Se comunque la sua mano è ancora difficile da individuare, a Perugia Raffaello dovette vedere per la prima volta le grottesche, dipinte sul soffitto del Collegio, che entrarono in seguito nel suo repertorio iconografico.

Sembra però che la sua prima opera cui possa darsi un reale credito attributivo sia la Madonna col Bambino, affrescata nella stanza in cui si crede sia nato, in casa Santi a Urbino, databile al 1498 (e che fino a pochi anni addietro si riteneva opera del padre, che avrebbe raffigurato nei personaggi lo stesso Raffaello e la prima moglie Maria Ciarla).

Città di Castello (1499-1504)

Nel 1499 Raffaello, sedicenne, si trasferì con gli aiuti della bottega paterna a Città di Castello, dove ricevette la sua prima commissione indipendente: lo stendardo della Santissima Trinità per una confraternita locale che voleva offrire un’opera devozionale in segno di ringraziamento per la fine di una pestilenza proprio quell’anno. Il 10 dicembre 1500 infatti, Raffaello ed Evangelista da Pian di Meleto ottennero dalle monache del monastero di Sant’Agostino un nuovo incarico, che è il primo documentato della carriera dell’artista, la Pala del beato Nicola da Tolentino, terminata il 13 settembre 1501 e oggi dispersa in più musei dopo che venne sezionata in seguito a un terremoto nel 1789. Nel contratto è interessante notare come Raffaello, poco più che esordiente, venga già menzionato come magister Rafael Johannis Santis de Urbino.

A Città di Castello l’artista lasciò almeno altre due opere di rilievo, la Crocifissione Gavari e lo Sposalizio della Vergine.

Perugia e gli altri centri (1400-1500)

Nel frattempo la fama di Raffaello cominciava ad allargarsi a tutta l’Umbria, facendone uno dei più richiesti pittori attivi in regione. Nella sola Perugia, negli anni tra il 1501 e il 1505, gli vennero commissionate ben tre pale d’altare: la Pala Colonna, per la chiesa delle monache di Sant’Antonio, la Pala degli Oddi, per San Francesco al Prato e un’Assunzione della Vergine per le clarisse di Monteluce mai portata a termine, dipinta poi da Berto di Giovanni. Allo stesso periodo sono riferibili alcune Madonne col Bambino che, sebbene ancora ancorate all’esempio di Perugino, preludono già all’intenso e delicato rapporto tra madre e figlio dei più importanti capolavori successivi legati a questo tema. Tra queste spiccano Madonna Solly, la Madonna Diotallevi, la Madonna col Bambino tra i santi Girolamo e Francesco.

A Siena

A Siena fu invitato da Pinturicchio, con il quale intesseva una stretta amicizia. Il pittore più anziano invitò Raffaello a collaborare agli affreschi della Libreria Piccolomini, fornendo dei cartoni che svecchiassero il suo stile ormai in una fase di declino, come si vede nei precedenti affreschi della Cappella Baglioni a Spello.

Lo Sposalizio della Vergine (1504)

L’opera che conclude la fase giovanile, segnando un distacco ormai incolmabile con i modi del maestro Perugino, è lo Sposalizio della Vergine, datato 1504 e già conservato nella cappella Albizzini della chiesa di San Francesco di Città di Castello.

Il periodo fiorentino (1504-1508)

Raffaello si trovava a Siena, da Pinturicchio, quando gli giunse notizia delle straordinarie novità di Leonardo e Michelangelo impegnati rispettivamente agli affreschi della Battaglia di Anghiari e della Battaglia di Cascina. Desideroso di mettersi subito in viaggio, si fece preparare una lettera di presentazione da Giovanna Feltria, sorella del duca di Urbino e moglie del duca di Senigallia e “prefetto” di Roma. Nella lettera, datata 1º ottobre 1504 e indirizzata al gonfaloniere a vita Pier Soderini, si raccomanda il giovane figlio di Giovanni Santi. Probabilmente la lettera voleva assicurare qualche commissione ufficiale al giovane pittore, ma il gonfaloniere era in ristrettezze economiche per il recente esborso per acquistare il David di Michelangelo e i grandiosi progetti per la Sala del Gran Consiglio. Nonostante ciò non passò molto tempo che l’artista riuscì a garantirsi commissioni da alcuni facoltosi cittadini soprattutto residenti in Oltrarno, come Lorenzo Nasi, per il quale dipinse la Madonna del Cardellino, suo cognato Domenico Canigiani (per cui fece la Sacra Famiglia Canigiani), i Tempi (Madonna Tempi) e i coniugi Agnolo e Maddalena Doni.

Il soggiorno fiorentino fu di fondamentale importanza nella formazione di Raffaello, permettendogli di approfondire lo studio dei modelli quattrocenteschi (Masaccio, Donatello,…) nonché delle ultime conquiste di Leonardo e di Michelangelo. I suoi lavori a Firenze erano destinati quasi esclusivamente a committenti privati, gradualmente sempre più conquistati dalla sua arte; creò numerose tavole di formato medio-piccolo per la devozione privata, soprattutto Madonne e Sacre famiglie, e alcuni intensi ritratti.

Commissioni dall’Umbria

Ma all’inizio del soggiorno fiorentino erano soprattutto le commissioni che continuavano ad arrivare da Urbino e dall’Umbria a tenere occupato l’artista, che di tanto in tanto si spostava in quelle zone temporaneamente. Nel 1503 aveva ricevuto l’incarico, dalle monache del convento di Sant’Antonio a Perugia, di una pala d’altare, la Pala Colonna, che ebbe una lunga elaborazione, visibile nelle differenze di stile tra la lunetta ancora «umbra» e il gruppo «fiorentino» della tavola centrale.

Un’altra commissione ricevuta da Perugia, nel 1504, riguardò una Madonna col Bambino e i santi Giovanni Battista e Nicola (Pala Ansidei) da collocare in una cappella della chiesa di San Fiorenzo, che fu completata, secondo quanto sembra leggersi nel dipinto, nel 1505.

Commissioni dalle Marche

Nel 1505-1506 Raffaello dovette trovarsi brevemente a Urbino, dove venne accolto alla corte di Guidobaldo da Montefeltro: la fama raggiunta nella sua città natale è testimoniata da una menzione lusinghiera nel Cortegiano di Baldassarre Castiglione e da un serie di ritratti, tra cui quello di Guidobaldo, di Elisabetta Gonzaga sua consorte e dell’erede designato del ducato Guidobaldo della Rovere.

Per il duca inoltre dipinse una grande Madonna e tre tavolette di soggetto.

La serie delle Madonne

Celebre è la serie delle Madonne col Bambino che a Firenze raggiunge nuovi vertici. Per famiglie fiorentine della borghesia medio-alta Raffaello dipinse alcuni capolavori assoluti, come alcuni gruppi di Madonne a tutta figura col Bambino e san Giovannino: la Bella giardiniera, la Madonna del Cardellino e la Madonna del Belvedere. In queste opere la figura della Vergine si erge monumentale davanti al paesaggio, dominandolo con leggiadria ed eleganza, mentre rivolge gesti affettuosi ai bambini, in strutture compositive piramidali di grande efficacia. Gesti familiari si riscontrano anche in opere come la Madonna d’Orleans, come quello di solleticare, o spontanei come nella Grande Madonna Cowper (Gesù allunga una mano verso il seno materno), o ancora sguardi intensi come nella Madonna Bridgewater.

I ritratti

Al periodo fiorentino appartengono infine alcuni ritratti nei quali è manifesta l’influenza di Leonardo: la Donna gravida, Agnolo Doni e Maddalena Strozzi, la Dama col liocorno e la Muta.

La pala Baglioni

Opera cruciale di questa fase è la Pala Baglioni (1507), commissionata da Atalanta Baglioni, in commemorazione dei fatti di sangue che avevano portato alla morte di suo figlio Grifonetto, e destinata a un altare nella chiesa di San Francesco al Prato a Perugia, anche se dipinta interamente a Firenze.

La Madonna del Baldacchino

Opera conclusiva del periodo fiorentino, del 1507-1508, può considerarsi la Madonna del Baldacchino, lasciata incompiuta per la sua repentina chiamata a Roma, da parte di Giulio II. Si tratta di una grande pala d’altare, la prima commissione del genere ricevuta a Firenze, con una sacra conversazione organizzata attorno al fulcro del trono della Vergine, con un fondale architettonico grandioso ma tagliato ai margini, in modo da amplificarne la monumentalità. Ogni staticità appare annullata dall’intenso movimento circolare di gesti e sguardi, esasperato poi negli angeli in volo accuratamente scorciati. Sant’Agostino ad esempio allunga un braccio verso sinistra invitando lo spettatore a percorrere con lo sguardo lo spazio semicircolare della nicchia, legando i personaggi uno per uno, caratteristica che a breve si ritroverà anche negli affreschi delle Stanze vaticane.

Il periodo romano (1509-1520)

Verso la fine del 1508 per Raffaello arrivò la chiamata a Roma che cambiò la sua vita. In quel periodo infatti papa Giulio II aveva messo in atto una straordinaria opera di rinnovo urbanistico e artistico della città in generale e del Vaticano in particolare, chiamando a sé i migliori artisti sulla piazza, tra cui Michelangelo e Donato Bramante. Fu proprio Bramante, secondo la testimonianza di Vasari, a suggerire al papa il nome del conterraneo Raffaello, ma non è escluso che nella sua chiamata ebbero un ruolo decisivo anche i Della Rovere, parenti del papa, in particolare Francesco Maria, figlio di quella Giovanna Feltria che già aveva raccomandato l’artista a Firenze.

Fu così che il Sanzio, appena venticinquenne, si trasferì velocemente a Roma, lasciando incompiuti alcuni lavori a Firenze.

La Stanza della Segnatura

Qui affiancò una squadra di pittori provenienti da tutta Italia (il Sodoma, Bramantino, Baldassarre Peruzzi, Lorenzo Lotto e altri) per la decorazione, da poco avviata, dei nuovi appartamenti papali, le Stanze. Le sue prove nella volta della prima, poi detta Stanza della Segnatura, piacquero così tanto al papa che decise di affidargli, fin dal 1509, tutta la decorazione dell’appartamento, a costo anche di distruggere quanto già era stato fatto, sia ora sia nel Quattrocento (tra cui gli affreschi di Piero della Francesca).

Alle pareti Raffaello decorò quattro grandi lunettoni, ispirandosi alle quattro facoltà delle università medioevali, ovvero teologia, filosofia, poesia e giurisprudenza. Opere celeberrime sono la Disputa del Sacramento, la Scuola di Atene o il Parnaso. In queste dispiegò una visione scenografica ed equilibrata, in cui le masse di figure si dispongono, con gesti naturali, in simmetrie solenni e calcolate, all’insegna di una monumentalità e una grazia che vennero poi definite “classiche”.

La Stanza di Eliodoro

Nel 1511, mentre i lavori alla Stanza della Segnatura andavano esaurendosi, Raffaello iniziò il primo degli affreschi, la Cacciata di Eliodoro dal Tempio, mostrando un radicale sviluppo stilistico, con l’adozione di un inedito stile “drammatico”, fatto di azioni concitate, pause e asimmetrie, impensabile nei pur recentissimi affreschi della stanza precedente. Nella Messa di Bolsena tornano ritmi pacati, anche se la profondità dell’architettura e gli effetti luminosi creano un’innovativa drammaticità; il colore si arricchì di campiture dense e più corpose, forse derivate dall’esempio dei pittori veneti attivi alla corte papale. All’inizio del 1513 Giulio II morì, e il suo successore, Leone X, confermò tutti gli incarichi a Raffaello, affidandogliene presto anche di nuovi.

Per Agostino Chigi

Mentre la fama di Raffaello si andava espandendo, nuovi committenti desideravano avvalersi dei suoi servigi, ma solo quelli più influenti alla corte papale poterono riuscire a distoglierlo dai lavori in Vaticano. Tra questi spiccò sicuramente Agostino Chigi, ricchissimo banchiere di origine senese, che si era fatto costruire in quegli anni la prima e imitatissima villa urbana da Baldassarre Peruzzi, quella poi detta villa Farnesina.

Raffaello vi fu chiamato a lavorare a più riprese, prima con l’affresco del Trionfo di Galatea (1511), di straordinaria rievocazione classica, poi alla Loggia di Psiche (1518-1519) e infine alla camera con le Storie di Alessandro, opera incompiuta creata poi dal Sodoma.

Inoltre per i Chigi Raffaello eseguì l’affresco delle Sibille e angeli (1514) in Santa Maria della Pace e soprattutto l’ambizioso progetto della Cappella Chigi in Santa Maria del Popolo, dove l’artista curò anche la progettazione dell’architettura, i cartoni per i mosaici della cupola e, probabilmente, i disegni per le sculture, raffiguranti i profeti Giona ed Elia, eseguite dal Lorenzetto e completate, anni dopo, da Gianlorenzo Bernini.

I ritratti

Accanto all’attività di frescante, un’altra delle fondamentali occupazioni di quegli anni è legata ai ritratti, dove apportò molteplici innovazioni sul tema. Già nel Ritratto di cardinale oggi al Prado, il Ritratto di Baldassarre Castiglione il Ritratto di Fedra Inghirami .

Ma fu soprattutto con il Ritratto di Giulio II che le innovazioni si fecero più evidenti, con un punto di vista diagonale e leggermente dall’alto, studiato come se lo spettatore si trovasse in piedi accanto al pontefice. L’atteggiamento di malinconica pensosità, così indicatore della situazione politica dell’epoca (il 1512), introduce un elemento psicologico fino ad allora estraneo dalla ritrattistica ufficiale. In pratica lo spettatore è come se si trovasse al cospetto del pontefice, senza alcun distacco fisico o psicologico.

Un’impostazione simile venne replicata anche nel Ritratto di Leone X con i cardinali Giulio de’ Medici e Luigi de’ Rossi (1518-19, Uffizi).

La Fornarina

Sempre agli stessi anni (1518-19) risale il celeberrimo ritratto di donna noto come La Fornarina, opera di dolce e immediata sensualità unita a vivida luminosità. Secondo una ricostruzione priva di fondamento scientifico e documentale, l’artista vi avrebbe ritratto seminuda la sua musa-amante, sull’identificazione della quale sono poi fiorite romantiche leggende. Il termine “Fornarina” rimandi a una tradizione linguistica consolidata, in cui “forno” e derivati (“fornaio”, “fornaia”, “infornare”, ecc.) indicano metaforicamente l’organo sessuale femminile e le pratiche connesse all’accoppiamento.

La bottega

Per far fronte alla sua crescita di popolarità e alla conseguente mole di lavoro richiesto, Raffaello mise su una grande bottega, strutturata come una vera e propria impresa capace di dedicarsi a incarichi sempre più impegnativi e nel minor tempo possibile, garantendo comunque un alto livello qualitativo. Prese così all’apprendistato non solo garzoni e artisti giovani, ma anche maestri già affermati e di talento.

Allievi fedeli e duttili furono Tommaso Vincidor, Vincenzo Tamagni o Guillaume de Marcillat, mentre aggiungevano alla bottega un bagaglio di conoscenze polivalenti, dall’architettura alla scultura, personalità come Lorenzo Lotti.

Giovan Francesco Penni fu un vero e proprio factotum della bottega, capace di imitare i modelli del maestro alla perfezione, tanto che è difficile distinguere la sua migliore produzione grafica da quella di Raffaello; la sua scarsa inventiva però lo rese una figura di secondo piano dopo la scomparsa del maestro. L’allievo più conosciuto e quello capace poi di avere la migliore carriera artistica indipendente fu Giulio Romano, che dopo la morte del maestro si trasferì a Mantova diventando uno dei massimi interpreti del manierismo italiano. Un altro allievo affermato fu Perin del Vaga, fiorentino dallo stile elegante e accentuatamente disegnativo, che dopo il Sacco di Roma si trasferì a Genova dove ebbe un ruolo fondamentale nella diffusione locale del linguaggio raffaellesco.

Stanza dell’Incendio di Borgo

Nelle Stanze Leone X non fece altro che confermare a Raffaello il ruolo che aveva sotto il suo predecessore. La terza Stanza, poi detta dell’Incendio di Borgo, fu incentrata sulla celebrazione del pontefice in carica attraverso le figure di suoi omonimi predecessori, come Leone III e IV. La lunetta più famosa, nonché l’unica con il consistente intervento diretto del maestro, è quella dell’Incendio di Borgo (1514) in cui cominciano ormai a essere evidenti i debiti verso il dinamismo turbinoso degli affreschi di Michelangelo, reinterpretati però con altri influssi, fino a generare un nuovo “classicismo”, scenografico e monumentale, ma dotato anche di grazia e armonia.

Gli arazzi per la Sistina

Le imprese che distolsero il Sanzio dall’esecuzione materiale degli affreschi nella terza Stanza furono essenzialmente la nomina a sovrintendente della basilica vaticana dopo la morte di Bramante (11 aprile 1514) e quella degli arazzi per la Cappella Sistina. Leone X desiderava infatti legare anche il proprio nome alla prestigiosa impresa della Cappella pontificia, facendo decorare l’ultima fascia rimasta libera, il registro più basso dove si trovavano i finti tendaggi e dove decise di far tessere a Bruxelles una serie di arazzi da appendere in occasione delle liturgie più solenni. La prima notizia sulla commissione risale al 15 giugno 1515.

Raffaello, trovandosi a confronto direttamente con i grandi maestri del Quattrocento e soprattutto con Michelangelo e la sua sfolgorante volta, dovette aggiornare il proprio stile, adattandosi anche alle difficoltà tecniche dell’impresa che prevedevano la stesura di cartoni rovesciati rispetto al risultato finale, la limitazione della gamma cromatica rispetto alle tinture disponibili dei filati e il dover rinunciare ai dettagli troppo minuti, preferendo grandi campiture di colore.

Nei sette su dieci cartoni conservati oggi al Victoria and Albert Museum di Londra si nota come il Sanzio seppe superare tutte queste difficoltà, semplificando la determinazione dei piani in profondità e scandendo con maggiore forza l’azione grazie a una netta contrapposizione tra gruppi e figure isolate e ricorrendo a gesti eloquenti, di immediata leggibilità, all’insegna di uno stile “tragico” ed esemplare.

Commissioni inevase

Nonostante la velocità e l’efficienza della bottega, la notevole consistenza degli aiuti e l’eccellente organizzazione lavorativa, la fama di Raffaello andava ormai ben oltre le reali possibilità di soddisfare le richieste e molte commissioni, anche importanti, dovettero essere a lungo rimandate o inevase.

Raffaello architetto

Quando Raffaello decise di accettare l’incarico di soprintendente ai lavori nella basilica vaticana, il più importante cantiere romano, egli aveva già alle spalle alcune esperienze in questo campo. Le stesse architetture dipinte, sfondo di tante celebri opere, mostrano un bagaglio di conoscenze che va di là dal consueto apprendistato di un pittore.

Basilica di San Pietro

Fu così che Raffaello si dedicò al cantiere di San Pietro con entusiasmo, ma anche con un certo timore, come si legge dal carteggio di quegli anni, per la dimensione dei suoi slanci che vorrebbero eguagliare la perfezione degli antichi. Non a caso si fece fare da Fabio Calvo una traduzione del De architectura di Vitruvio, rimasta inedita, per poter studiare direttamente il trattato e utilizzarlo nello studio sistematico dei monumenti romani.

Sebbene i lavori procedessero con lentezza (Leone X era infatti molto meno interessato del suo predecessore al nuovo edificio), suo fu il fondamentale contributo di ripristinare il corpo longitudinale della basilica, da innestare sulla crociera avviata da Bramante.

Nella progettazione Raffaello utilizzò un nuovo sistema, quello della proiezione ortogonale (dice: l’architetto non ha bisogno di saper disegnare come un pittore, ma di avere disegni che gli permettono di vedere l’edificio così com’è), abbandonando la configurazione prospettica del Bramante.

Villa Madama

Un altro progetto, destinato a trovare grande risonanza e sviluppi per tutto il Cinquecento, fu quello incompiuto di Villa Madama alle pendici del Monte Mario, iniziatosi nel 1518 su incarico di Leone X e del cardinale Giulio de’ Medici. L’impostazione rinascimentale della villa venne rielaborata alla luce della lezione dell’antico, con forme imponenti e una particolare attenzione all’integrazione tra edificio e ambiente naturale circostante. Attorno al cortile centrale circolare si dovevano dipartire una serie di assi visivi o di percorso, in un susseguirsi di logge, saloni, ambienti di servizio e locali termali, fino al giardino alle pendici del monte, con ippodromo, teatro, stalle per duecento cavalli, fontane e giochi d’acqua. Delicatamente calibrata è la decorazione, in cui si fondono affreschi e stucchi ispirati alla Domus Aurea e ad altri resti archeologici scoperti in quell’epoca.

L’opera venne sospesa all’epoca di Clemente VII e danneggiata durante il Sacco di Roma.

La morte

Raffaello morì il 6 aprile 1520, a soli 37 anni, nel giorno di Venerdì Santo. Secondo Vasari la morte sopraggiunse dopo quindici giorni di malattia, iniziatasi con una febbre “continua e acuta”, causata secondo il biografo da “eccessi amorosi”, e inutilmente curata con ripetuti salassi.

Nella camera ove egli morì era stata appesa, alcuni giorni prima della morte, la Trasfigurazione e la visione di quel capolavoro generò ancora più sconforto per la sua perdita. Scrisse Vasari a tal proposito: «La quale opera, nel vedere il corpo morto e quella viva, faceva scoppiare l’anima di dolore a ognuno che quivi guardava».

La sua scomparsa fu salutata dal commosso cordoglio dell’intera corte pontificia. Il suo corpo fu sepolto nel Pantheon, come egli stesso aveva richiesto. In seguito, le sue spoglie furono riesumate, e fu realizzato un calco del suo teschio, tuttora esposto e conservato nella sua casa natale.

ITALIAN MAILES 21-22-23-24 ^ issue of 20 July 2020 of a sheet with n.4 stamps dedicated to Raffaello Sanzio, in the 5th centenary of the disappearance

On 20 July 2020, the Ministry of Economic Development with the Italian Post Office issues ordinary stamps belonging to the thematic series “The Italian artistic and cultural heritage” dedicated to Raffaello Sanzio, on the fifth centenary of the disappearance, relating to the value of tariff B zone 2 50 g, corresponding to € 3.90 each.

Vignettes: the four stamps, enclosed in a sheet, reproduce respectively a work by Raffaello Sanzio and precisely, starting from the top, from left to right:

- Self-portrait – UffizivGalleries, Florence

- Triumph of Galatea – Villa Farnesina, Rome

- Madonna and Child – Raphael’s Birthplace, Urbino

- Marriage of the Virgin – Pinacoteca di Brera, Milan.

- date 20 July 2020

- indentation 11

- gravure printing

- type of paper white self-adhesive neutral coated paper

- printed I.P.Z.S. Rome

- print run 200,000

- sheet size 185 x 130 mm

- value B zona 2 50 g = €3.90 each

- sketcher: T. Trinca and edited by the Philatelic Center of the Operational Directorate of the Istituto Poligrafico e Zecca dello Stato S.p.A.

- num. catalog leaflet Michel YT UN

- num. catalog Self Portrait Michel YT UN

- num. catalog Triumph of Galatea Michel YT UN

- num. catalog Madonna and Child Michel YT UN

- num. catalog Marriage of the Virgin Michel YT UN

If you are interested in purchasing this leaflet, you can buy it for € 20.00. Send me a request to the email: protofilia1@gmail.com

Raffaello Sanzio (Urbino, March 28 or April 6, 1483 – Rome, April 6, 1520) was an Italian painter and architect, among the most famous of the Renaissance. Considered one of the greatest artists of all time, his work marked an essential path for all subsequent painters and was of vital importance for the development of the artistic language of the centuries to come, giving life, inter alia, to a school that art “in his own way” and which goes by the name of mannerism.

Biography

Youth (1483-1504)

Origins (1483-1493)

Raphael was born in Urbino “the year 1483, on Good Friday, at three in the morning, by a certain Giovanni de ‘Santi, a painter no less excellent, but a man of good talent, and able to direct his children to that good way, which luckily for him, it had not been shown to him in his beautiful youth. Raphael was the first and only son of Giovanni Santi and Nicola Ciarla’s Battista Magic. The surname “Sanzio” is in fact only one of the possible variations of “Santi”, in particular derived from the Latin “Sancti” with which Raffaello will then usually, in maturity, sign his works.

First artistic training

The fact that he was born and spent his youth in Urbino, which at that time was an artistic center of primary importance that radiated the ideals of the Renaissance in Italy and Europe, was instrumental in the formation of Raphael. Raphael probably learned the first lessons of drawing and painting from his father, who at least from the eighties of the fifteenth century was in charge of a thriving workshop, engaged in the creation of works for the local aristocracy. In his father’s workshop, the very young Raffaello learned the basics of artistic techniques, including probably the fresco technique: one of the very first works attributed to him is in fact the Madonna di Casa Santi, delicate mural painting in the family home.

First meeting with Perugino

It is not known through which streets the young man from Urbino became part of the Perugino workshop: in fact, the news of Vasari does not seem credible, according to which Raphael was a pupil of Perugino even before the death of his father and even that of his mother.

Apprenticeship by Perugino (1494-1498)

The first traces of Raphael’s presence next to Perugino are linked to some works in his workshop between 1497 and the new century. In particular, it was decided to see an intervention by Raphael in the tablet of the Nativity of the Madonna in the predella of the Pala di Fano (1497) and in some figures of the frescoes of the Collegio del Cambio in Perugia (from 1498), especially where the masses of color take on almost a plastic value and the way of delimiting the light and shadow parts is accentuated, with a general thickening of the contours. If however his hand is still difficult to locate, in Perugia Raphael had to see for the first time the grotesques, painted on the ceiling of the College, which later entered his iconographic repertoire.

However, it seems that his first work to which a real credit can be attributed is the Madonna and Child, frescoed in the room in which he is believed to have been born, in the Santi house in Urbino, datable to 1498 (and which until a few years ago was considered a work of his father, who would have depicted Raphael himself and his first wife Maria Ciarla in the characters).

Città di Castello (1499-1504)

In 1499 Raffaello, sixteen, moved with the help of his father’s workshop to Città di Castello, where he received his first independent commission: the banner of the Holy Trinity for a local brotherhood that wanted to offer a devotional work as a sign of thanks for the end of a pestilence just that year. On 10 December 1500, in fact, Raphael and Evangelista da Pian di Meleto obtained a new assignment from the nuns of the monastery of Sant’Agostino, which is the first documented of the artist’s career, the altarpiece of Blessed Nicola da Tolentino, completed on 13 September 1501 and now dispersed in several museums after it was dissected following an earthquake in 1789. In the contract it is interesting to note how Raphael, little more than a beginner, is already mentioned as magister Rafael Johannis Santis de Urbino.

In Città di Castello the artist left at least two other important works, the Crucifixion Gavari and the Marriage of the Virgin.

Perugia and the other towns (1400-1500)

In the meantime, Raphael’s fame began to spread to all of Umbria, making him one of the most requested active painters in the region. In Perugia alone, in the years between 1501 and 1505, three altarpieces were commissioned: the Pala Colonna, for the church of the nuns of Sant’Antonio, the Pala degli Oddi, for San Francesco al Prato and a Assumption of the Virgin for the Poor Clares of Monteluce never completed, then painted by Berto di Giovanni. At the same time some Madonnas with the Child are referable which, although still anchored to Perugino’s example, already prelude to the intense and delicate relationship between mother and son of the most important later masterpieces related to this theme. Among these stand out Madonna Solly, Madonna Diotallevi, Madonna and Child between Saints Jerome and Francis.

In Siena

In Siena he was invited by Pinturicchio, with whom he developed a close friendship. The older painter invited Raffaello to collaborate on the frescoes of the Piccolomini Library, supplying cartoons that rejuvenated his style by now in a phase of decline, as seen in the previous frescoes of the Baglioni Chapel in Spello.

The Marriage of the Virgin (1504)

The work that concludes the youthful phase, marking a detachment now unbridgeable with the ways of the master Perugino, is the Marriage of the Virgin, dated 1504 and already preserved in the Albizzini chapel of the church of San Francesco in Città di Castello.

The Florentine period (1504-1508)

Raffaello was in Siena, from Pinturicchio, when he received news of the extraordinary novelties of Leonardo and Michelangelo engaged respectively in the frescoes of the Battle of Anghiari and of the Battle of Cascina. Eager to set off immediately, he had a presentation letter prepared by Giovanna Feltria, sister of the Duke of Urbino and wife of the Duke of Senigallia and “prefect” of Rome. In the letter, dated 1 October 1504 and addressed to the life-long gonfalonier Pier Soderini, the young son of Giovanni Santi is recommended. Probably the letter wanted to secure some official commission to the young painter, but the gonfalonier was in financial straits for the recent outlay to buy Michelangelo’s David and the grand plans for the Sala del Gran Consiglio. Despite this, it wasn’t long before the artist managed to secure commissions from some wealthy citizens, especially residents of Oltrarno, such as Lorenzo Nasi, for whom he painted the Madonna del Cardellino, his brother-in-law Domenico Canigiani (for which he made the Holy Family Canigiani), the Tempi (Madonna Tempi) and the spouses Agnolo and Maddalena Doni.

The Florentine stay was of fundamental importance in the formation of Raphael, allowing him to deepen the study of the fifteenth-century models (Masaccio, Donatello, …) as well as the latest conquests of Leonardo and Michelangelo. His works in Florence were destined almost exclusively to private clients, gradually more and more conquered by his art; he created numerous medium-small size tables for private devotion, especially Madonnas and Holy families, and some intense portraits.

Commissions from Umbria

But at the beginning of the Florentine stay it was above all the commissions that continued to arrive from Urbino and Umbria to keep the artist busy, who occasionally moved to those areas temporarily. In 1503 he had been commissioned by the nuns of the convent of Sant’Antonio in Perugia, an altarpiece, the Pala Colonna, which had a long elaboration, visible in the style differences between the still “Umbrian” lunette and the “Florentine” group of the central table.

Another commission received from Perugia, in 1504, concerned a Madonna and Child with Saints John the Baptist and Nicholas (Pala Ansidei) to be placed in a chapel of the church of San Fiorenzo, which was completed, according to what seems to be read in the painting, in 1505 .

Commissions from the Marche

In 1505-1506 Raphael had to find himself briefly in Urbino, where he was welcomed at the court of Guidobaldo da Montefeltro: the fame achieved in his hometown is evidenced by a flattering mention in the Cortegiano by Baldassarre Castiglione and by a series of portraits, including that of Guidobaldo, by Elisabetta Gonzaga his consort and the designated heir of the duchy Guidobaldo della Rovere.

He also painted a large Madonna and three subject tablets for the Duke.

The Madonnas series

Famous is the series of Madonnas with the Child who reaches new heights in Florence. For Florentine families of the middle-upper middle class, Raphael painted some absolute masterpieces, such as groups of full-length Madonnas with the Child and Saint John: the Bella Giardiniera, the Madonna del Cardellino and the Madonna del Belvedere. In these works the figure of the Virgin stands monumentally in front of the landscape, dominating it with gracefulness and elegance, while addressing affectionate gestures to children, in highly effective pyramidal compositional structures. Familiar gestures are also found in works such as the Madonna d’Orleans, such as that of tickling, or spontaneous as in the Great Madonna Cowper (Jesus extends a hand towards the mother’s breast), or even intense looks like in the Madonna Bridgewater.

The portraits

Finally, some portraits in which the influence of Leonardo is manifested belong to the Florentine period: the pregnant woman, Agnolo Doni and Maddalena Strozzi, the lady with the unicorn and the suit.

The Baglioni altarpiece

The crucial work of this phase is the Pala Baglioni (1507), commissioned by Atalanta Baglioni, in commemoration of the blood events that led to the death of his son Grifonetto, and intended for an altar in the church of San Francesco al Prato in Perugia, also if painted entirely in Florence.

The Madonna del Baldacchino

The final work of the Florentine period, dated 1507-1508, can be considered the Madonna del Baldacchino, left unfinished due to its sudden call to Rome by Julius II. It is a large altarpiece, the first commission of its kind received in Florence, with a sacred conversation organized around the fulcrum of the Virgin’s throne, with a grandiose architectural backdrop but cut on the margins, in order to amplify its monumentality. Every static appears to be canceled by the intense circular movement of gestures and glances, exasperated then in the carefully shortened angels in flight. For example, Sant’Agostino stretches an arm to the left inviting the viewer to look around the semicircular space of the niche, binding the characters one by one, a feature that will shortly be found also in the frescoes of the Vatican Rooms.

The Roman period (1509-1520)

Towards the end of 1508 the call to Rome arrived for Raffaello which changed his life. In fact, at that time Pope Julius II had carried out an extraordinary urban and artistic renewal of the city in general and of the Vatican in particular, calling the best artists on the square, including Michelangelo and Donato Bramante. It was Bramante himself, according to Vasari’s testimony, who suggested to the pope the name of the fellow countryman Raffaello, but it is not excluded that in his call the Della Rovere, relatives of the pope, in particular Francesco Maria, son of that Giovanna, also played a decisive role. Feltria who had already recommended the artist in Florence.

So it was that Sanzio, barely 25 years old, moved quickly to Rome, leaving some works unfinished in Florence.

The Room of the Segnatura

Here he joined a team of painters from all over Italy (Sodoma, Bramantino, Baldassarre Peruzzi, Lorenzo Lotto and others) for the recently launched decoration of the new papal apartments, the Stanze. His rehearsals in the vault of the first, later called Stanza della Segnatura, pleased the pope so much that he decided to entrust him, since 1509, all the decoration of the apartment, even at the cost of destroying what had already been done, both now and in the Quattrocento (including the frescoes by Piero della Francesca).

On the walls Raphael decorated four large lunettes, inspired by the four faculties of medieval universities, namely theology, philosophy, poetry and jurisprudence. Famous works are the Dispute of the Sacrament, the School of Athens or the Parnassus. In these he unfolded a scenographic and balanced vision, in which the masses of figures arrange themselves, with natural gestures, in solemn and calculated symmetries, in the name of a monumentality and grace which were then defined as “classic”.

The room of heliodorus

In 1511, while the work on the Stanza della Segnatura was running out, Raphael began the first of the frescoes, the Expulsion of Heliodorus from the Temple, showing a radical stylistic development, with the adoption of an unprecedented “dramatic” style, made of agitated actions, pauses and asymmetries, unthinkable in the very recent frescoes of the previous room. Quiet rhythms return to the Mass of Bolsena, even if the depth of the architecture and the lighting effects create an innovative drama; the color was enriched with dense and full-bodied backgrounds, perhaps derived from the example of the Venetian painters active in the papal court. At the beginning of 1513 Julius II died, and his successor, Leo X, confirmed all the assignments to Raphael, soon entrusting him with new ones too.

For Agostino Chigi

While Raphael’s fame was expanding, new patrons wished to avail himself of his services, but only those most influential in the papal court were able to divert him from the work in the Vatican. Among these, Agostino Chigi certainly stood out, a very rich banker of Sienese origin, who had the first and much-imitated urban villa built by Baldassarre Peruzzi in those years, the one later called villa Farnesina.

Raphael was called to work on several occasions, first with the fresco of the Triumph of Galatea (1511), of extraordinary classical re-enactment, then at the Loggia di Psiche (1518-1519) and finally at the room with the Stories of Alexander, unfinished work then created by Sodom.

Furthermore, for the Chigi family, Raphael painted the Sibyls and angels (1514) in Santa Maria della Pace and above all the ambitious project of the Chigi Chapel in Santa Maria del Popolo, where the artist also took care of the design of the architecture, the cartoons for the mosaics of the dome and, probably, the drawings for the sculptures, depicting the prophets Jonah and Elia, executed by Lorenzetto and completed, years later, by Gianlorenzo Bernini.

The portraits

Alongside the fresco business, another of the fundamental occupations of those years is linked to portraits, where he made multiple innovations on the theme. Already in the Portrait of Cardinal today in the Prado, the Portrait of Baldassarre Castiglione the Portrait of Fedra Inghirami.

But it was above all with the Portrait of Julius II that the innovations became more evident, with a diagonal point of view and slightly from above, studied as if the spectator was standing next to the pontiff. The attitude of melancholy thoughtfulness, thus an indicator of the political situation of the time (1512), introduces a psychological element hitherto unrelated to official portraiture. In practice, the spectator is as if he were in the presence of the pontiff, without any physical or psychological detachment.

A similar approach was also replicated in the Portrait of Leo X with cardinals Giulio de ‘Medici and Luigi de’ Rossi (1518-19, Uffizi).

La Fornarina

Also in the same years (1518-19), the famous portrait of a woman known as La Fornarina dates back, a work of sweet and immediate sensuality combined with vivid brightness. According to a reconstruction without scientific and documentary foundation, the artist would have portrayed his muse-lover half-naked, on the identification of which romantic legends then flourished. The term “Fornarina” refers to a consolidated linguistic tradition, in which “oven” and derivatives (“baker”, “baker”, “baking”, etc.) metaphorically indicate the female sexual organ and the practices related to mating.

The shop

To cope with his growth in popularity and the consequent amount of work required, Raffaello set up a large shop, structured as a real company capable of dedicating himself to increasingly demanding assignments and in the shortest possible time, while still guaranteeing a high quality level . Thus he took apprenticeship not only young boys and artists, but also established and talented masters. Faithful and flexible students were Tommaso Vincidor, Vincenzo Tamagni or Guillaume de Marcillat, while they added to the workshop a wealth of multipurpose knowledge, from architecture to sculpture, personalities such as Lorenzo Lotti. Giovan Francesco Penni was a real factotum of the workshop, capable of imitating the master’s models to perfection, so much so that it is difficult to distinguish his best graphic production from that of Raphael; his poor inventiveness, however, made him a second-rate figure after the master’s disappearance. The best known pupil and the one capable of having the best independent artistic career was Giulio Romano, who after the master’s death moved to Mantua becoming one of the greatest interpreters of Italian mannerism. Another well-known pupil was Perin del Vaga, a Florentine with an elegant and accentuated design style, who after the Sack of Rome moved to Genoa where he played a fundamental role in the local diffusion of Raphael’s language.

Borgo Fire Room

Leone X in the Stanze did nothing but confirm to Raffaello the role he had under his predecessor. The third room, later called the Borgo Fire, was centered on the celebration of the pontiff in office through the figures of his namesake predecessors, such as Leo III and IV. The most famous lunette, as well as the only one with the consistent direct intervention of the master, is that of the Borgo Fire (1514) in which the debts towards the swirling dynamism of Michelangelo’s frescoes begin to be evident, reinterpreted however with other influences , until generating a new “classicism”, scenographic and monumental, but also endowed with grace and harmony.

The tapestries for the Sistine

The undertakings that diverted Sanzio from the material execution of the frescoes in the third room were essentially the appointment as superintendent of the Vatican basilica after Bramante’s death (11 April 1514) and that of the tapestries for the Sistine Chapel. Leo X in fact also wished to link his name to the prestigious enterprise of the Pontifical Chapel, by decorating the last band left free, the lowest register where the fake curtains were located and where he decided to weave a series of tapestries in Brussels to hang in occasion of the most solemn liturgies. The first news on the commission dates back to June 15, 1515.

Raphael, finding himself directly confronted with the great masters of the fifteenth century and especially with Michelangelo and his brilliant vault, had to update his style, also adapting to the technical difficulties of the company which involved the drafting of inverted cartons with respect to the final result, the limitation of the chromatic range compared to the available yarn dyes and having to give up too minute details, preferring large backgrounds of color.

In the seven out of ten cartoons preserved today at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, it is known how Sanzio was able to overcome all these difficulties, simplifying the determination of the plans in depth and punctuating the action with greater force thanks to a clear contrast between groups and isolated figures and resorting to eloquent gestures, of immediate legibility, in the name of a “tragic” and exemplary style.

Unpaid commissions

Despite the speed and efficiency of the shop, the remarkable consistency of the help and the excellent work organization, Raphael’s fame now went well beyond the real possibilities of satisfying the requests and many commissions, even important ones, had to be postponed for a long time or unanswered.

Raffaello architect

When Raphael decided to accept the post of superintendent of the works in the Vatican basilica, the most important Roman construction site, he already had some experiences in this field behind him. The same painted architectures, the background of many famous works, show a wealth of knowledge that goes beyond the usual apprenticeship of a painter.

Basilica of Saint Peter

So it was that Raphael dedicated himself to the construction site of San Pietro with enthusiasm, but also with a certain fear, as can be read from the correspondence of those years, for the size of his impulses that would like to match the perfection of the ancients. It was not by chance that Fabio Calvo had a translation of Vitruvius’ De architectura, which remained unpublished, in order to study the treatise directly and use it in the systematic study of Roman monuments.

Although the work proceeded slowly (Leo X was in fact much less interested than his predecessor in the new building), his was the fundamental contribution to restore the longitudinal body of the basilica, to be inserted on the cruise started by Bramante.

In designing Raffaello used a new system, that of orthogonal projection (he says: the architect does not need to know how to draw like a painter, but to have drawings that allow him to see the building as it is), abandoning the perspective configuration of Bramante.

Villa Madama

Another project, destined to find great resonance and developments throughout the sixteenth century, was the unfinished one of Villa Madama on the slopes of Monte Mario, which started in 1518 on behalf of Leone X and Cardinal Giulio de ‘Medici. The Renaissance setting of the villa was reworked in the light of the lesson of the ancient, with imposing shapes and a particular attention to the integration between the building and the surrounding natural environment. Around the circular central courtyard a series of visual or path axes had to depart, in a succession of loggias, lounges, service areas and thermal rooms, up to the garden on the slopes of the mountain, with a racecourse, theater, stables for two hundred horses, fountains and water games [39]. The decoration is delicately calibrated, in which frescoes and stuccos inspired by the Domus Aurea and other archaeological remains discovered at that time blend.

The work was suspended at the time of Clement VII and damaged during the Sack of Rome.

The death

Raphael died on April 6, 1520, at only 37 years old, on Good Friday. According to Vasari, death occurred after fifteen days of illness, which began with a “continuous and acute” fever, caused according to the biographer by “amorous excesses”, and unnecessarily treated with repeated bloodletting.

In the room where he died, a few days before his death, the Transfiguration and the vision of that masterpiece had generated even more discomfort for his loss. Vasari wrote in this regard: “Which work, in seeing the dead body and the living one, made the soul burst with pain to everyone who looked at it.”

His disappearance was greeted by the emotional condolence of the entire papal court. His body was buried in the Pantheon, as he himself had requested. Later, his remains were exhumed, and a cast of his skull was made, still exposed and preserved in his birthplace.

If you are interested in purchasing this leaflet, you can buy it for € 20.00. Send me a request to the email: protofilia1@gmail.com