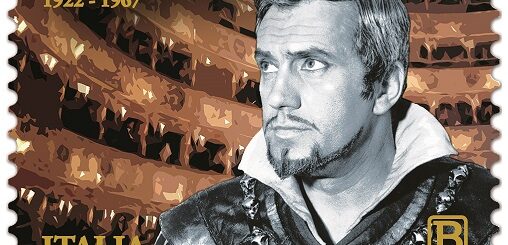

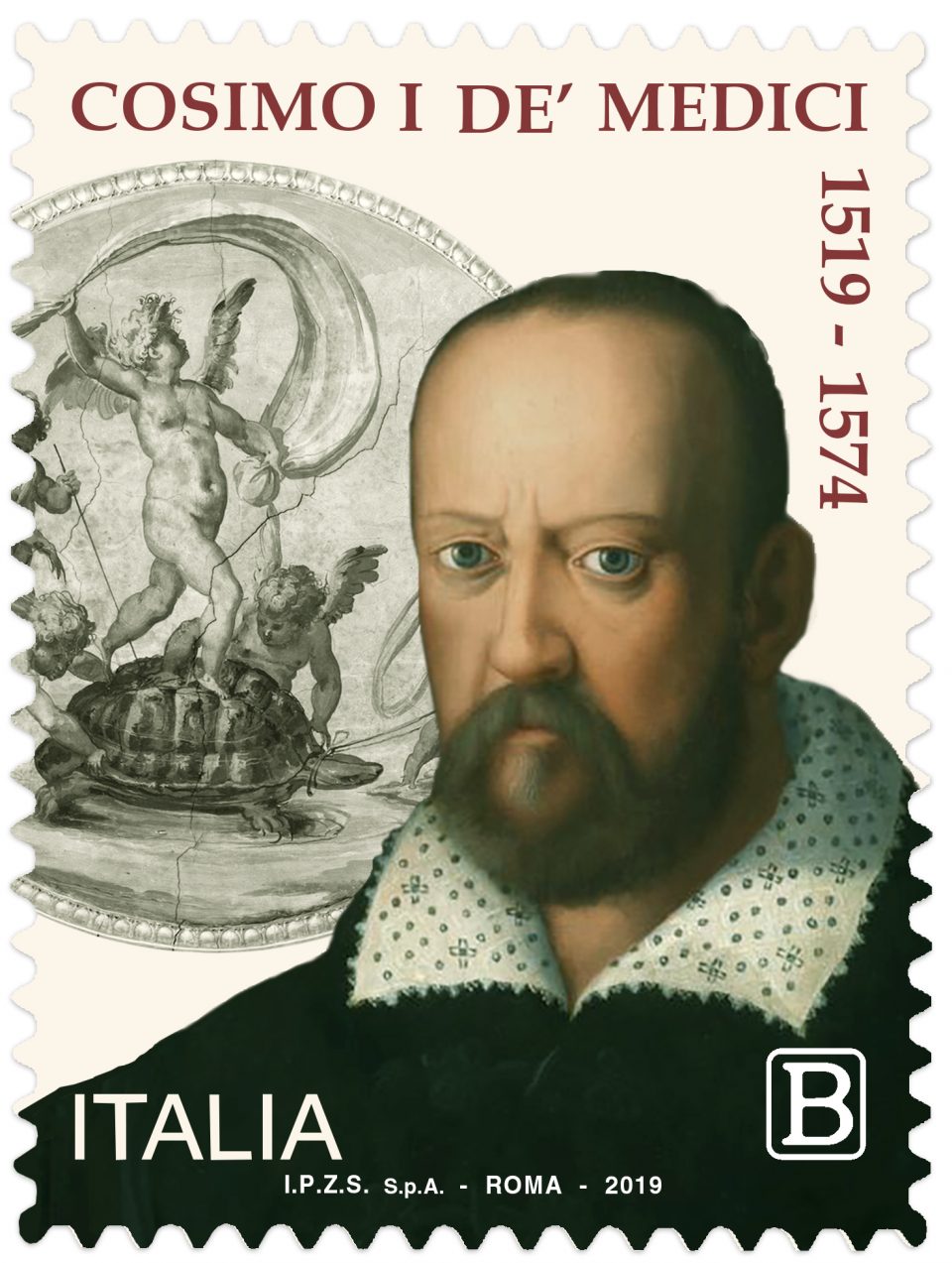

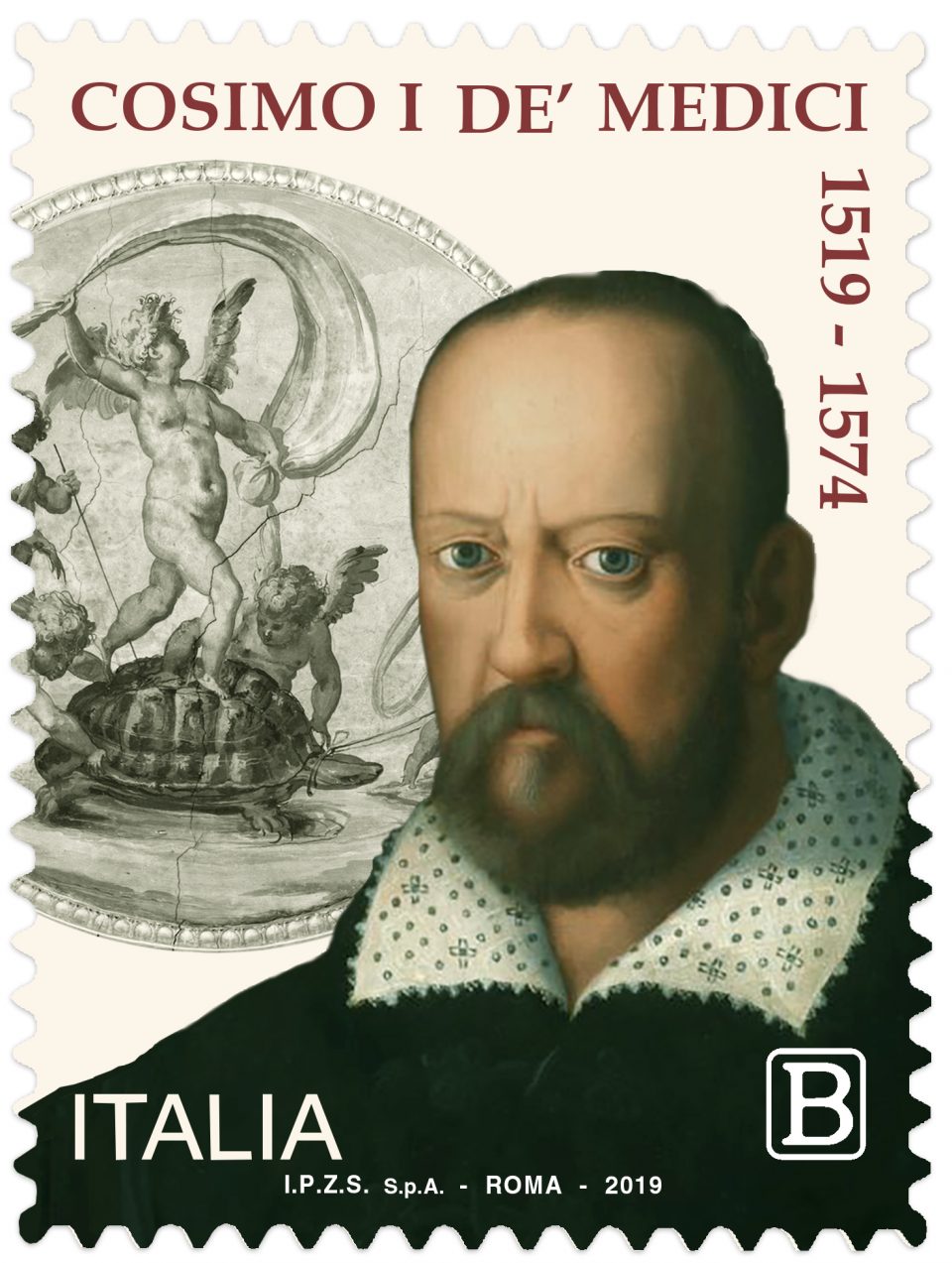

POSTE ITALIANE 30^ emissione del 12 giugno 2019 di un francobollo commemorativo di Cosimo I de’ Medici, nel V centenario della nascita.

POSTE ITALIANE 30^ emissione del 12 giugno 2019 di un francobollo commemorativo di Cosimo I de’ Medici, nel V centenario della nascita.

Il Ministero dello Sviluppo ha emesso il 12 giugno 2019 un francobollo commemorativo di Cosimo I de’ Medici, nel V centenario della nascita, relativo al valore della tariffa B, corrispondente ad €1.10.

- data / date 12 giugno 2019

- dentellatura / serration 11

- stampa / printing fustellatura/rotocalco

- tipo di carta / paper type bianca patinata neutra

- stampato / printed I.P.Z.S. Roma

- tiratura / edition 2.500.000

- fogli / sheet 45

- dimensioni / dimension 30 x 40 mm

- costo / price B= €1.10

- bozzettista / designer

- num. catalogo Mic. 4127 YT 3888 UN 3970

Cosimo I de’ Medici (Firenze, 12 giugno 1519 – Firenze, 21 aprile 1574) è stato il secondo ed ultimo Duca di Firenze, dal 1537 al 1569, e, in seguito all’elevazione del Ducato di Firenze a Granducato di Toscana, il primo Granduca di Toscana, dal 1569 alla morte, avvenuta nel 1574.

Figlio del condottiero Giovanni de’ Medici, detto delle Bande Nere, e di Maria Salviati, apparteneva per via paterna al ramo cadetto dei Medici detto dei Popolani, discendente da quel Lorenzo de’ Medici detto il Vecchio, fratello di Cosimo il Vecchio, il primo Signore de facto di Firenze; mentre era discendente per via materna dal ramo principale stesso, in quanto la madre era figlia di Lucrezia de’ Medici, a sua volta figlia di Lorenzo il Magnifico, Signore di Firenze. In questo modo Cosimo I portò al potere il ramo cadetto dei Popolani e diede vita alla linea granducale.

Biografia

La conquista del potere

Cosimo salì al potere nel 1537, a soli 17 anni, dopo l’assassinio del duca di Firenze Alessandro de’ Medici. Il delitto fu ordito da Lorenzino de’ Medici, lontano cugino del duca Alessandro che, tuttavia, non seppe cogliere l’occasione di sostituirsi al proprio parente e finì col fuggire da Firenze. Nessuna delle famiglie più importanti sembrava essere in grado di prendere il posto dei Medici quando Cosimo, allora pressoché sconosciuto, apparve in città, seguito da pochi servi.

Egli veniva dal Mugello dove era cresciuto dopo la morte del padre e riuscì a farsi nominare duca nonostante appartenesse ad un ramo secondario della famiglia. Infatti, vista la sua giovane età ed il suo contegno modesto, molti personaggi influenti della Firenze del tempo speravano di avere a che fare con un giovane debole, svagato, attratto solamente dalla caccia e dalle donne; una persona facile da influenzare. Cosimo venne, quindi, nominato capo del governo con la clausola che il potere sarebbe stato esercitato dal consiglio dei Quarantotto. Ma Cosimo aveva interamente ereditato lo spirito battagliero del padre e della nonna paterna Caterina Sforza.

Infatti, appena investito del potere e dopo aver ottenuto un decreto che escludeva il ramo di Lorenzino da qualsiasi diritto di successione, esautorò i consiglieri ed assunse l’assoluta autorità. Restaurò il potere dei Medici in modo così saldo che da quel momento governarono Firenze e gran parte della Toscana attuale fino alla fine della dinastia, avvenuta con la morte senza eredi dell’ultimo granduca Medici, Gian Gastone, nel 1737; la struttura del governo creata da Cosimo, durò fino alla proclamazione del Regno d’Italia.

Il governo autoritario di Cosimo indusse alcuni importanti cittadini all’esilio volontario. Essi radunarono le loro forze e col supporto della Francia e degli stati vicini di Firenze, nel tentativo di rovesciare militarmente il governo fiorentino, alla fine del luglio 1537 marciarono su Firenze sotto la guida di Piero Strozzi.

Quando Cosimo seppe che si stavano avvicinando, inviò le sue migliori truppe, comandate da Alessandro Vitelli, a bloccare i nemici. Lo scontro avvenne nei pressi della rocca di Montemurlo il 1º agosto 1537 e, dopo aver sconfitto l’armata degli esuli, il Vitelli assaltò il castello, dove lo Strozzi ed i suoi compari si erano rifugiati. L’assedio durò solamente poche ore e terminò con la caduta degli assediati, dando a Cosimo la sua prima vittoria militare.

I capi della rivolta furono dapprima imprigionati e poi decapitati nel palazzo del Bargello. Per tutta la sua vita Cosimo agì in modo spietato contro chi cercava di opporsi ai suoi piani. Occorre precisare che il suo dispotismo si rivolgeva in massima parte a coloro che ponevano in discussione la sua autorità, e quindi non il popolo, ma quei nobili e ricchi borghesi fiorentini che non tolleravano la sua supremazia e il suo potere. In questa etica assolutista è da includere anche la distruzione iniziata il 20/10/1561 da parte di Cosimo I della pregevole Cattedrale di Arezzo, posta fuori dalle mura della città, al Colle del Pionta, per esservi lì fortificato Piero Strozzi il 20/07/1554.

Matrimonio

Inizialmente Cosimo cercò di sposare Margherita d’Austria, figlia dell’imperatore e vedova del duca Alessandro. Ma non ottenne che un secco rifiuto e la pretesa che alla vedova fosse versata una cospicua parte del patrimonio dei Medici. Abbandonato questo progetto, sposò nel 1539 Eleonora di Toledo, figlia di Don Pedro Alvarez de Toledo, marchese di Villafranca e viceré spagnolo di Napoli. Si incontrarono per la prima volta nella villa di Poggio a Caiano e si sposarono con grandi fasti nella chiesa di San Lorenzo: lui aveva 20 anni e lei 17. Grazie a questo matrimonio Cosimo entrò in possesso delle enormi ricchezze della moglie e si garantì l’amicizia politica del viceré di Napoli, uno dei più fidati luogotenenti dell’imperatore. Il Bronzino eseguì molti ritratti di Eleonora, il più famoso dei quali è conservato agli Uffizi.

Assieme a Cosimo Eleonora ebbe undici figli, assicurando così in teoria la successione e la possibilità di combinare matrimoni con altre importanti case regnanti, anche se l’unico che sopravvisse in maniera duratura fu Ferdinando I. Eleonora morì nel 1562 all’età di soli quarant’anni, assieme ai suoi figli Giovanni e Garzia. I tre furono uccisi dalla malaria, contratta durante un viaggio verso Pisa, dove volevano curarsi dalla tubercolosi, malattia dovuta all’insalubre situazione cittadina, per sfuggire alla quale proprio Eleonora aveva comprato la residenza di Palazzo Pitti in Oltrarno.

I primi anni di governo

Già dal 1537, iniziò l’inarrestabile ascesa autoritaria di Cosimo I, che inviò a Carlo V il vescovo di Forlì, Bernardo Antonio de Medici, per informarlo di quanto avvenuto alla morte di Alessandro e della successione da parte dello stesso Cosimo, ma soprattutto per confermargli fedeltà , allo scopo di ottenere la conferma imperiale. A partire dal 1543, dopo avere riscattato le ultime fortezze ancora in mano all’Imperatore, Cosimo I, secondo un disegno sistematico commisurato alle particolari condizioni dello Stato Toscano esposto ai frequenti passaggi di truppe e, minacciato di dentro dal banditismo e dai fuoriusciti fiorentini, avviò una sorprendente attività edilizio-militare:

- Intraprese la realizzazione di nuovi presidi costruendo fortezze a Siena, ad Arezzo, a Sansepolcro e a Pistoia. A Sansepolcro, inoltre, fece abbattere tutti i borghetti esterni alle mura, che si espandevano su di una superficie considerevole e ospitavano vari edifici, tra cui chiese e ospedali, preferendo fortificare l’antica cerchia muraria piuttosto che allargarla;

- Rafforzò le difese di origine medioevale a Pisa, a Volterra e a Castrocaro, in Romagna, a pochi chilometri da Forlì;

- Fece erigere una nuova cinta muraria a Fivizzano a sbarramento dei passi appenninici della Cisa e del Cerreto;

- Fece fortificare San Piero a Sieve, Empoli, Cortona e Montecarlo ai confini della Repubblica di Lucca;

- Fece costruire ex novo la città-fortezza di Portoferraio (Cosmopoli) nell’Isola d’Elba e piazze d’armi quali Sasso di Simone nel Montefeltro e Terra del Sole (Eliopoli), tra la vecchia fortezza di Castrocaro, destinata ad essere abbandonata, e Forlì, quindi ai confini con lo Stato della Chiesa.

Come indica il nome, Terra del Sole doveva costituire non un semplice luogo fortificato ma addirittura un piccolo esperimento di città ideale. La breve distanza da Forlì (meno di 10 km) indica, da un lato, la forte penetrazione del potere di Firenze in Romagna (la cosiddetta “Romagna toscana”); dall’altro, costituiva un abisso incolmabile perché il capoluogo romagnolo non cadde mai in potere dei fiorentini e segna, quindi, l’estremo limite della loro espansione.

Altra priorità di Cosimo fu la ricerca di una posizione di maggior indipendenza rispetto alle forze europee. Egli abbandonò la tradizionale posizione di Firenze, di norma alleata con i francesi, per operare dalla parte dell’imperatore Carlo V. I ripetuti aiuti finanziari che Cosimo garantì all’impero gli valsero il ritiro delle guarnigioni imperiali da Firenze e Pisa ed una sempre maggior indipendenza politica.

Il timore di nuovi attentati alla sua persona lo spinsero a crearsi una piccola legione di guardia del corpo personale, composta da svizzeri. Nel 1548 a Venezia Cosimo riuscì a far uccidere Lorenzino de’ Medici per mano di Giovanni Francesco Lottini che assoldò due sicari volterrani. Per anni lo aveva fatto inseguire per tutta Europa e con la sua morte tramontava ogni possibile pretesa dinastica contro di lui sul comando della Toscana. L’anno successivo mediò uno scontro tra Siena e l’impero facendo accettare l’indipendenza della città in cambio della presenza di una guarnigione spagnola al suo interno.

Preferì non intraprendere la conquista di Lucca, fermato dal timore che i lucchesi, gelosi della loro indipendenza, si sarebbero trasferiti altrove con i loro capitali rovinando il commercio della città (come del resto era avvenuto in precedenza con la conquista di Pisa). D’altro canto Lucca, unica città imperiale italiana, godeva, anche grazie alla propria ricchezza, di importanti appoggi da parte di potenti stati europei e tentare la sua conquista avrebbe potuto avere effetti imprevedibili sugli equilibri internazionali. Andarono a vuoto, invece, i suoi tentativi per ottenere Pontremoli e la Corsica che, pur di sottrarsi dal dominio genovese, avrebbe accettato l’unione con la Toscana, con la quale aveva, se non altro, vincoli culturali e linguistici più profondi.

Sapendo di non essere granché amato dai fiorentini, egli li tenne fuori dall’esercito, quindi disarmati, e arruolò truppe solo provenienti dagli altri suoi domìni.

La conquista di Siena

Nell 1552 Siena si ribellò contro l’impero, scacciò la guarnigione spagnola e fece occupare la città dai francesi. Nel 1553 una spedizione militare, inviata dal viceré di Napoli Don Pedro, aveva tentato di riconquistare la città ma, complice anche la morte dello stesso viceré, l’impresa era stata un fallimento. Nel 1554 Cosimo ottenne il supporto dell’imperatore per muover guerra contro Siena utilizzando il proprio esercito. Dopo alcune battaglie nelle campagne tra le due città e la sconfitta dei senesi a Marciano, Siena fu assediata dai fiorentini. Il 17 aprile 1555, passati molti mesi di assedio, la città, stremata, cadde: la popolazione senese era diminuita da 40.000 a 6.000 abitanti.

Siena rimase sotto protezione imperiale fino al 1557, quando il figlio dell’imperatore, Filippo II di Spagna, la cedette a Cosimo, tenendo per sé i territori di Orbetello, Porto Ercole, Talamone,Monte Argentario e Porto Santo Stefano, che andarono a formare lo Stato dei Presidi. Nel 1559, su decreto del Trattato di Cateau-Cambrésis al termine delle Guerre d’Italia franco-spagnole, Cosimo ottenne anche i residui territori della Repubblica di Siena riparata in Montalcino, ultimo presidio dei senesi sotto protezione francese.

L’organizzazione dello stato

Sebbene Cosimo esercitasse il potere in modo dispotico, sotto la sua amministrazione la Toscana fu uno stato al passo coi tempi. Esautorò da ogni carica, anche formale, la maggior parte delle importanti famiglie fiorentine, non fidandosi dei loro componenti. Scelse piuttosto funzionari di umili origini. Una volta ottenuto il titolo di Granduca di Toscana da Papa Pio V nel 1569, mantenne la divisione giuridica ed amministrativa tra il Ducato di Firenze (il cosiddetto “Stato vecchio”) ed il Ducato di Siena (detto “Stato Nuovo”, quindi tenendo le due zone sapientemente separate e con magistrature proprie. Rinnovò l’amministrazione della giustizia, facendo emanare un nuovo codice criminale. Rese efficienti i magistrati e la polizia. Le sue carceri erano tra le più temute d’Italia.

Spostò la sua dimora da Palazzo Medici (oggi Palazzo Medici Riccardi) a Palazzo Vecchio, in modo che ogni fiorentino avesse ben chiaro che il potere era tutto nelle sue mani. Anni più tardi si trasferì a Palazzo Pitti.

Introdusse e finanziò la fabbricazione di arazzi. Costruì strade, opere di prosciugamento, porti. Dotò molte città toscane di fortilizi. Rafforzò l’esercito, istituì nel 1561 l’Ordine marinaresco di Santo Stefano con sede a Pisa nel vasariano Palazzo dei Cavalieri e migliorò la flotta toscana, partecipando alla battaglia di Lepanto. Promosse le attività economiche, sia recuperando antiche lavorazioni (come l’estrazione dei marmi a Seravezza), sia di nuove. I continui aumenti delle tasse, seppur controbilanciati da un incremento dei commerci, posero il germe di uno scontento popolare che si acuirà sempre di più con i suoi successori. Nonostante le difficoltà economiche, fu molto prodigo come mecenate.

Proseguì, inoltre, gli studi di alchimia e di scienze esoteriche, la cui passione aveva ereditato dalla nonna Caterina Sforza.

Negli ultimi dieci anni del suo regno rinunciò alla conduzione degli affari interni dello stato in favore di suo figlio Francesco.

Granduca

Cosimo si adoperò per ricevere un titolo regale che lo affrancasse dalla condizione di semplice feudatario dell’imperatore e che gli desse quindi maggior indipendenza politica. Non trovando alcun appoggio da parte imperiale si rivolse al Papato. Già con Paolo IV aveva cercato di ottenere il titolo di re o arciduca, ma invano. Finalmente, Nel 1569, dopo aver stipulato un accordo col Papa secondo il quale avrebbe messo la sua flotta a servizio della Lega Santa che si stava venendo a formare per contrastare l’avanzata ottomana, Pio V emanò una bolla che lo creava granduca di Toscana. Nel gennaio dell’anno successivo fu incoronato dal papa stesso a Roma. In realtà tale diritto sarebbe spettato all’imperatore e per questo Spagna e Austria si rifiutarono di riconoscere il nuovo titolo minacciando di abbandonare la Lega, mentre Francia ed Inghilterra lo ritennero subito valido e col passare del tempo tutti gli stati europei finirono per riconoscerlo. Alcuni storici ipotizzano che l’avvicinamento tra Pio V e la conseguente concessione dell’ambito titolo granducale avvenisse con la consegna a tradimento dell’eretico Pietro Carnesecchi, che era rifugiato a Firenze confidando nella protezione del Duca medesimo.

Gli ultimi anni

La morte della moglie nel 1562 e di due dei suoi figli colpiti da malaria lo aveva profondamente segnato. Nel 1564 abdicò a favore del figlio Francesco, ritirandosi nella villa di Castellovicino a Firenze. Guardando anche il profilo umano, c’è da credere che la vita nelle sale ormai vuote di Palazzo Pitti, già occupate dall’amatissima moglie e dai numerosi figli che non gli erano sopravvissuti, lo deprimesse enormemente.

Dopo aver frequentato Eleonora degli Albizi, dalla quale ebbe due figli naturali, nel 1570 Cosimo prese in seconde nozze Camilla Martelli come moglie morganatica, che gli diede una figlia, poi legittimata e integrata nella successione. Il peggioramento del suo burrascoso carattere ed i continui scontri con i figli (Francesco aveva una visione dello Stato completamente diversa dal padre), a causa della nuova moglie, resero i suoi ultimi anni turbolenti. Morì il 21 aprile 1574, a cinquantacinque anni, già gravemente menomato da un ictus che gli aveva limitato la mobilità e tolto la parola.

Se sei interessato all’acquisto del francobollo lo puoi acquistare al prezzo di € 1.50. Inviami una richiesta alla email: protofilia1@gmail.com

ITALIAN POSTE 30th issue of 12 June 2019 of a commemorative stamp of Cosimo I de ‘Medici, in the fifth centenary of the birth.

Cosimo I de ‘Medici (Florence, 12 June 1519 – Florence, 21 April 1574) was the second and last Duke of Florence, from 1537 to 1569, and, following the elevation of the Duchy of Florence to the Grand Duchy of Tuscany, the first Grand Duke of Tuscany, from 1569 to his death in 1574.

Son of the condottiere Giovanni de ‘Medici, known as delle Bande Nere, and of Maria Salviati, he belonged by fatherly to the cadet branch of the Medici known as dei Popolani, a descendant of that Lorenzo de’ Medici known as the Elder, brother of Cosimo il Vecchio, the first De facto Lord of Florence; while he was descendant through his mother’s main branch, since his mother was the daughter of Lucrezia de ‘Medici, in turn the daughter of Lorenzo the Magnificent, Lord of Florence. In this way Cosimo I brought the cadet branch of the Popolani to power and gave life to the grand ducal line.

Biography

The conquest of power

Cosimo came to power in 1537, only 17, after the assassination of the Duke of Florence Alessandro de ‘Medici. The crime was hatched by Lorenzino de ‘Medici, a distant cousin of Duke Alessandro who, however, did not know how to take the opportunity to replace his relative and ended up fleeing Florence. None of the most important families seemed to be able to take the place of the Medici when Cosimo, then almost unknown, appeared in the city, followed by a few servants.

He came from Mugello where he grew up after his father’s death and managed to get himself named duke despite belonging to a secondary branch of the family. In fact, given his young age and his modest demeanor, many influential figures of the Florence of the time hoped to deal with a weak, distracted young man, attracted only by hunting and women; a person easy to influence. Cosimo was then appointed head of the government with the clause that the power would be exercised by the council of the Forty-eight. But Cosimo had entirely inherited the fighting spirit of his father and paternal grandmother Caterina Sforza.

In fact, having just been invested with power and having obtained a decree that excluded the Lorenzino branch from any right of succession, he renounced the councilors and assumed absolute authority. He restored the power of the Medici so firmly that from that time they ruled Florence and much of modern Tuscany until the end of the dynasty, which occurred with the death without heirs of the last Grand Duke Medici, Gian Gastone, in 1737; the structure of the government created by Cosimo lasted until the proclamation of the Kingdom of Italy.

Cosimo’s authoritarian government led some important citizens to voluntary exile. They gathered their forces and with the support of France and the neighboring states of Florence, in an attempt to militarily overthrow the Florentine government, at the end of July 1537 they marched on Florence under the gu When Cosimo learned that they were approaching, he sent his best troops, commanded by Alessandro Vitelli, to block the enemies. The battle took place near the fortress of Montemurlo on 1 August 1537 and, after defeating the army of the exiles, Vitelli assaulted the castle, where Strozzi and his cronies had taken refuge. The siege lasted only a few hours and ended with the fall of the besieged, giving Cosimo his first military victory.

The leaders of the revolt were first imprisoned and then beheaded in the Bargello palace. Throughout his life Cosimo acted ruthlessly against those who tried to oppose his plans. It should be pointed out that his despotism was addressed mostly to those who questioned his authority, and therefore not the people, but those noble and rich Florentine bourgeois who did not tolerate his supremacy and his power. In this absolutist ethic is to include also the destruction started on 10/20/1561 by Cosimo I of the valuable Cathedral of Arezzo, placed outside the city walls, at Colle del Pionta, to be there fortified Piero Strozzi on 20/07 / 1554.

Marriage

Initially Cosimo tried to marry Margherita of Austria, daughter of the emperor and widow of the duke Alessandro. But he obtained only a dry refusal and the claim that a large part of the Medici heritage was paid to the widow. Having abandoned this project, in 1539 he married Eleanor of Toledo, daughter of Don Pedro Alvarez de Toledo, marquis of Villafranca and Spanish viceroy of Naples. They met for the first time in the villa of Poggio a Caiano and married with great pomp in the church of San Lorenzo: he was 20 years old and she was 17. Thanks to this marriage Cosimo came into possession of the enormous wealth of his wife and secured himself the political friendship of the viceroy of Naples, one of the emperor’s most trusted lieutenants. Bronzino executed many portraits of Eleonora, the most famous of which is preserved in the Uffizi.

Together with Cosimo Eleonora he had eleven children, thus ensuring in theory the succession and the possibility of combining marriages with other important ruling houses, even if the only one who survived in a lasting way was Ferdinando I. Eleonora died in 1562 at the age of only forty years, together with his sons Giovanni and Garzia. The three were killed by malaria, contracted during a trip to Pisa, where they wanted to cure themselves of tuberculosis, a disease caused by the unhealthy city situation, to escape to which Eleonora had bought the residence of Palazzo Pitti in Oltrarno.

The first years of government

As early as 1537, began the unstoppable authoritarian rise of Cosimo I, who sent the bishop of Forlì, Bernardo Antonio de Medici, to Charles V to inform him of what happened to the death of Alexander and the succession by Cosimo himself, but above all to confirm his loyalty, in order to obtain imperial confirmation. Beginning in 1543, after having redeemed the last fortresses still held by the Emperor, Cosimo I, according to a systematic design commensurate with the particular conditions of the Tuscan State exposed to frequent troop passes and, threatened from within by banditry and exiles, he started a surprising construction-military activity:

• Undertook the construction of new garrisons by building fortresses in Siena, Arezzo, Sansepolcro and Pistoia. In Sansepolcro, moreover, he had all the suburbs outside the walls demolished, which expanded over a considerable area and housed various buildings, including churches and hospitals, preferring to fortify the ancient city walls rather than widen them;

• It strengthened the defenses of medieval origin in Pisa, Volterra and Castrocaro, in Romagna, a few kilometers from Forlì;

• He built a new city wall in Fivizzano as a barrier against the Apennine passes of Cisa and Cerreto;

• He had San Piero a Sieve, Empoli, Cortona and Montecarlo fortified at the borders of the Republic of Lucca;

• He built the fortress-town of Portoferraio (Cosmopoli) in the Island of Elba from scratch, and squares of arms such as Sasso di Simone in Montefeltro and Terra del Sole (Eliopoli), between the old fortress of Castrocaro, destined to be abandoned , and Forlì, therefore on the borders with the State of the Church.idance of Piero Strozzi. As the name indicates, Terra del Sole was not a simple fortified place but even a small experiment in an ideal city. The short distance from Forlì (less than 10 km) indicates, on the one hand, the strong penetration of the power of Florence in Romagna (the so-called “Tuscan Romagna”); on the other, it constituted an unbridgeable chasm because the Romagna capital never fell into the hands of the Florentines and therefore marks the extreme limit of their expansion.

Another priority of Cosimo was the search for a position of greater independence with respect to European forces. He abandoned the traditional position of Florence, normally allied with the French, to operate on the side of the Emperor Charles V. The repeated financial aid that Cosimo granted to the empire earned him the withdrawal of the imperial garrisons from Florence and Pisa and an ever greater one political independence.

The fear of new attacks on his person led him to create a small legion of personal bodyguard, composed of Swiss. In 1548 in Venice Cosimo managed to have Lorenzino de ‘Medici killed by Giovanni Francesco Lottini who hired two Sicilian assassins. For years he had made him chase all over Europe and with his death set any possible dynastic claim against him on the command of Tuscany. The following year he mediated a clash between Siena and the empire by accepting the independence of the city in exchange for the presence of a Spanish garrison within it.

He preferred not to undertake the conquest of Lucca, stopped by the fear that the Lucchesi, jealous of their independence, would have moved elsewhere with their capitals ruining the commerce of the city (as indeed had happened previously with the conquest of Pisa). On the other hand, Lucca, the only Italian imperial city, enjoyed important support from powerful European states thanks to its wealth, and attempting to conquer it could have had unforeseeable effects on international balances. Instead, his attempts to obtain Pontremoli and Corsica failed, which, in order to escape from the Genoese domination, would have accepted the union with Tuscany, with which he had, if nothing else, deeper cultural and linguistic bonds.

Knowing that he was not much loved by the Florentines, he kept them out of the army, then disarmed, and enlisted troops only from his other domains.

The conquest of Siena

n 1552 Siena rebelled against the empire, drove out the Spanish garrison and had the city occupied by the French. In 1553 a military expedition, sent by the viceroy of Naples Don Pedro, had tried to reconquer the city but, also because of the death of the same viceroy, the enterprise had been a failure. In 1554 Cosimo obtained the support of the emperor to wage war against Siena using his own army. After some battles in the countryside between the two cities and the defeat of the Sienese at Marciano, Siena was besieged by the Florentines. On April 17, 1555, after many months of siege, the city, exhausted, fell: the Sienese population had decreased from 40,000 to 6,000 inhabitants.

Siena remained under imperial protection until 1557, when the emperor’s son, Philip II of Spain, sold it to Cosimo, taking for himself the territories of Orbetello, Porto Ercole, Talamone, Monte Argentario and Porto Santo Stefano, which they went to form the State of the Presidia. In 1559, by decree of the Treaty of Cateau-Cambrésis at the end of the Franco-Spanish Italian Wars, Cosimo also obtained the residual territories of the Republic of Siena repaired in Montalcino, the last garrison of the Sienese under French protection.

The organization of the state

Although Cosimo exercised power in a despotic manner, under his administration, Tuscany was a state in step with the times. He withdrew from every office, even formal, most of the important Florentine families, not trusting their members. He chose rather officials of humble origins. Once he obtained the title of Grand Duke of Tuscany from Pope Pius V in 1569, he maintained the legal and administrative division between the Duchy of Florence (the so-called “Old State”) and the Duchy of Siena (called the “New State”, thus keeping the two areas wisely separated and with their own magistrates, the administration of justice was renewed, a new criminal code was issued, the magistrates and the police were efficient, and their prisons were among the most feared in Italy.

He moved his home from Palazzo Medici (now Palazzo Medici Riccardi) to Palazzo Vecchio, so that every Florentine could understand that power was all in his hands. Years later he moved to Palazzo Pitti.

He introduced and financed the manufacture of tapestries. He built roads, drainage works, ports. He endowed many Tuscan cities with small fortresses. He strengthened the army, established in 1561 the maritime order of Santo Stefano based in Pisa in the Vasari Palace of the Knights and improved the Tuscan fleet, participating in the battle of Lepanto. He promoted economic activities, both by recovering ancient processes (such as the extraction of marble in Seravezza), and new ones. The constant increases in taxes, even if offset by an increase in trade, put the germ of a popular discontent that will become more and more acute with its successors. Despite the economic difficulties, he was very generous as a patron.

He also continued his studies in alchemy and esoteric sciences, whose passion he had inherited from his grandmother Caterina Sforza.

In the last ten years of his reign he renounced the conduct of internal affairs of the state in favor of his son Francesco.

Grand Duke

Cosimo strove to receive a royal title that freed him from the condition of a simple feudal lord of the emperor and therefore gave him greater political independence. Finding no support from the imperial, he turned to the Papacy. Already with Paul IV he had tried to obtain the title of king or archduke, but in vain. Finally, in 1569, after having entered into an agreement with the Pope according to which he would put his fleet at the service of the Holy League that was coming to form to oppose the Ottoman advance, Pius V issued a bull that created him Grand Duke of Tuscany. In January of the following year he was crowned by the Pope himself in Rome. In reality this right would have belonged to the emperor and for this Spain and Austria refused to recognize the new title threatening to leave the League, while France and England immediately considered it valid and over time all European states ended up recognizing it. Some historians hypothesize that the approach between Pius V and the consequent granting of the coveted grand-ducal title took place with the treasonable delivery of the heretic Pietro Carnesecchi, who was a refugee in Florence trusting in the protection of the Duke himself.

The last years

The death of his wife in 1562 and of two of his sons affected by malaria had deeply affected him. In 1564 he abdicated in favor of his son Francesco, retiring in the villa of Castellovicino in Florence. Looking also at the human profile, one must believe that life in the now empty halls of Palazzo Pitti, already occupied by his beloved wife and by the numerous children who had not survived him, depressed him enormously. After attending Eleonora degli Albizi, with whom he had two natural sons, Cosimo took second-hand marriage to Camilla Martelli as a morganatic wife, who gave him a daughter, then legitimized and integrated into the succession. The worsening of his stormy character and the continuous clashes with his children (Francesco had a vision of the State completely different from his father), due to his new wife, made his last years turbulent. He died on April 21, 1574, at the age of fifty-five, already severely impaired by a stroke that limited his mobility and took the floor.

If you are interested in buying the stamp you can buy it for € 1.50. Send me a request to the email: protofilia1@gmail.com

- data / date 12 giugno 2019

- dentellatura / serration 11

- stampa / printing fustellatura/rotocalco

- tipo di carta / paper type bianca patinata neutra

- stampato / printed I.P.Z.S. Roma

- tiratura / edition 2.500.000

- fogli / sheet 45

- dimensioni / dimension 30 x 40 mm

- costo / price B= €1.10

- bozzettista / designer

- num. catalogo Mic. 4127 YT 3888 UN 3970