POSTE ITALIANE 28^ emissione del 09 Agosto 2020 di un francobollo commemorativo di Enzo Biagi, nel centenario della nascita

POSTE ITALIANE 28^ emissione del 09 Agosto 2020 di un francobollo commemorativo di Enzo Biagi, nel centenario della nascita

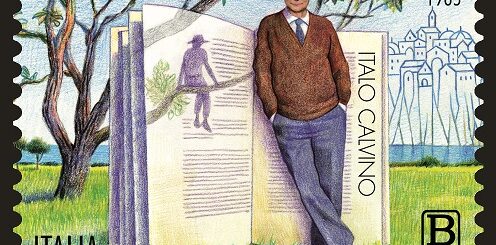

Poste Italiane comunica che oggi 9 agosto 2020 viene emesso dal Ministero dello Sviluppo Economico un francobollo commemorativo di Enzo Biagi, nel centenario della nascita, relativo al valore della tariffa B pari a 1,10€.

- data 09 agosto 2020

- dentellatura 11

- stampa rotocalcografia

- tipo di carta carta bianca patinata neutra -autoadesiva

- stampato I.P.Z.S. Roma

- tiratura 400.000

- dimensioni 40 x 30 mm

- valore B= €1.10

- bozzettista: a cura del Centro Filatelico della Direzione Operativa dell’Istituto Poligrafico e Zecca dello Stato S.p.A..

- num. catalogo Michel 4210 YT UN 4053

Se sei interessato all’acquisto di questo francobollo lo puoi acquistare al prezzo di € 1.50. Inviami una richiesta alla email: protofilia1@gmail.com

Enzo Marco Biagi (Pianaccio di Lizzano in Belvedere, 9 agosto 1920 – Milano, 6 novembre 2007) è stato un giornalista, scrittore, conduttore televisivo e partigiano italiano. È stato uno dei volti più popolari del giornalismo italiano del XX secolo.

Biografia

Gli Esordi

Nato nel piccolo borgo appenninico di Pianaccio, all’età di nove anni si trasferì a Bologna nel rione di Porta Sant’Isaia, dove il padre Dario (1891-1942) lavorava già da qualche anno come vice capo magazziniere in uno zuccherificio. L’idea di diventare giornalista nacque in lui dopo aver letto Martin Eden di Jack London. Frequentò l’istituto tecnico per ragionieri Pier Crescenzi, dove con altri compagni diede vita ad una piccola rivista studentesca, Il Picchio, che si occupava soprattutto di vita scolastica. Il Picchio fu soppresso dopo qualche mese dal regime fascista e da allora nacque in Biagi una forte indole antifascista. Nel 1937, all’età di diciassette anni, cominciò a collaborare con il quotidiano bolognese L’Avvenire d’Italia, occupandosi di cronaca, di colore e di piccole interviste a cantanti lirici. Il suo primo articolo fu dedicato al dilemma, vivo nella critica dell’epoca, se il poeta di Cesenatico Marino Moretti fosse o no crepuscolare. Nel 1940 fu assunto in pianta stabile dal Carlino Sera, edizione pomeridiana del Resto del Carlino, il principale quotidiano bolognese, come estensore di notizie, ovvero colui che si occupa di sistemare gli articoli portati in redazione (il lavoro di “cucina”, come si dice in gergo). Nel 1942 fu chiamato alle armi ma non partì per il fronte a causa di problemi cardiaci (che lo accompagneranno per tutta la vita). Il 18 dicembre 1943 si sposò con Lucia Ghetti, maestra elementare. Poco dopo fu costretto a rifugiarsi sulle montagne, dove aderì alla Resistenza combattendo nelle brigate Giustizia e Libertà legate al Partito d’Azione, di cui condivideva il programma e gli ideali. In realtà Biagi non combatté mai: il suo comandante, infatti, pur senza dubitare della sua fedeltà lo trovava troppo gracile. Prima gli diede compiti di staffetta, poi gli affidò la stesura di un giornale partigiano, Patrioti, di cui Biagi era in pratica l’unico redattore e con il quale informava la gente sul reale andamento della guerra lungo la Linea Gotica. Del giornale uscirono appena quattro numeri: la tipografia fu distrutta dai tedeschi. Biagi considerò sempre i mesi che passò da partigiano come i più importanti della sua vita: in memoria di ciò, volle che la sua salma fosse accompagnata al cimitero sulle note di Bella ciao. Terminata la guerra, Biagi entrò con le truppe alleate a Bologna e fu proprio lui ad annunciare dai microfoni del Psychological Warfare Branch alleato l’avvenuta liberazione. Poco dopo fu assunto come inviato speciale e critico cinematografico al Resto del Carlino che all’epoca aveva cambiato il suo nome in Giornale dell’Emilia. Nel 1946 seguì come inviato speciale il Giro d’Italia, nel 1947 partì per la Gran Bretagna dove raccontò il matrimonio della futura regina Elisabetta II. Fu il primo di una lunga serie di viaggi all’estero come “testimone del tempo” che contrassegneranno tutta la sua vita.

Gli anni cinquanta e sessanta

La prima direzione: Epoca

Nel 1951 si recò, per conto del Carlino, in Polesine dove, con una cronaca rimasta negli annali, descrisse l’alluvione che flagellava la provincia di Rovigo; nonostante il grande successo che riscossero quegli articoli, Biagi venne isolato all’interno del giornale per via di alcune sue dichiarazioni contrarie alla bomba atomica, che lo fecero passare per un comunista e che lo fecero considerare, quindi, un “pericoloso sovversivo” per il suo direttore. Gli articoli sul Polesine furono letti però anche da Bruno Fallaci, direttore del settimanale Epoca, alla ricerca di nuovi elementi per le sue redazioni. Fallaci lo chiamò a lavorare come caporedattore al periodico. Biagi e la sua famiglia (erano già nate due figlie, Bice e Carla; nel 1956 arriverà Anna) lasciarono quindi l’amata Bologna per Milano. Nel 1952 Epoca attraversava un momento difficile. Alla ricerca di scoop esclusivi da poter pubblicare in Italia, il nuovo direttore Renzo Segala, subentrato da un mese a Bruno Fallaci, decise di partire per l’America affidando a Biagi la guida del giornale per due settimane, stabilendo già in partenza i temi da affrontare durante la sua assenza e cioè il ritorno di Trieste all’Italia e l’inizio della primavera. Nel frattempo scoppiò però il “caso Wilma Montesi”: una giovane ragazza romana venne ritrovata morta sulla spiaggia di Ostia; ne nacque uno scandalo in cui rimase coinvolta l’alta borghesia laziale, il prefetto di Roma e Piero Piccioni, figlio del ministro Attilio Piccioni, il quale rassegnò le dimissioni. Biagi, intuendo la grande risonanza che il caso Montesi stava avendo nel Paese, decise, contro ogni disposizione, di dedicare a esso la copertina e di pubblicare un’inedita ricostruzione dei fatti. Fu un successo clamoroso: la tiratura di Epoca crebbe di oltre ventimila copie in una sola settimana e Mondadori tolse la direzione a Segàla, da poco tornato dagli Stati Uniti, affidandola proprio a Biagi. Sotto la direzione di Biagi, Epoca s’impose nel panorama delle grandi riviste italiane surclassando la storica concorrenza de l’Espresso e del’Europeo. La formula di Epoca, a quel tempo innovativa, punta a raccontare con riepiloghi e approfondimenti le notizie della settimana e le storie dell’Italia del boom. Un altro scoop esclusivo sarà la pubblicazione di fotografie che raffigurano un umanissimo papa Pio XII che gioca con un canarino. Nel 1960 un articolo sugli scontri di Genova e Reggio Emilia contro il governo Tambroni (che avevano provocato la morte di dieci operai in sciopero, tanto da essere definita strage di Reggio Emilia) provocò una dura reazione dello stesso governo, per cui Biagi fu costretto a lasciare Epoca. Qualche mese dopo fu assunto dalla Stampa come inviato speciale.

L’arrivo alla Rai: il Telegiornale

Il 1º ottobre 1961 divenne direttore del Telegiornale. Biagi si mise subito all’opera, applicando la formula di Epoca al TG, dando meno spazio alla politica e maggiormente ai “guai degli italiani”, come chiamava le mancanze del nostro sistema. Realizzò una memorabile intervista a Salvatore Gallo, l’ergastolano ingiustamente rinchiuso a Ventotene, la cui vicenda porterà in seguito il Parlamento ad approvare la revisione dei processi anche dopo la sentenza di cassazione. Dedicò servizi agli esperimenti nucleari dell’Unione Sovietica che avevano seminato il panico in tutta Europa. Fece assumere in Rai grandi giornalisti come Giorgio Bocca e Indro Montanelli, ma anche giovani come Enzo Bettiza ed Emilio Fede, destinati a una lunga carriera.

Nel novembre del 1961 arrivarono inevitabili le prime polemiche: il democristiano Guido Gonella, in un’interrogazione parlamentare al ministro dell’Interno Mario Scelba – poi passata alla storia per gli attacchi alle gambe nude delle gemelle Kessler, – accusò Enzo Biagi di essere fazioso e di “non essere allineato all’ufficialità”. Un’intervista in prima serata al leader comunistaPalmiro Togliatti gli procurò un duro attacco da parte dei giornali di destra, che iniziano una campagna aggressiva contro di lui.

Nel marzo del 1962 lanciò il primo rotocalco televisivo della televisione italiana: RT Rotocalco Televisivo. Apparve per la prima volta in video; il timido Biagi ricorderà sempre come un tormento le sue prime registrazioni. Condusse la trasmissione fino al 1968. A Roma tuttavia Biagi si sentiva con le mani legate. Le pressioni politiche erano insistenti; Biagi aveva già detto di no a Giuseppe Saragat, che gli proponeva alcuni servizi, ma resistere era difficile malgrado la solidarietà pubblica che gli arriva da personaggi celebri del periodo come Giovannino Guareschi, Garinei e Giovannini,Giangiacomo Feltrinelli, Liala e dallo stesso Bernabei.

| «Ero l’uomo sbagliato al posto sbagliato: non sapevo tenere gli equilibri politici, anzi proprio non mi interessavano e non amavo stare al telefono con onorevoli e sottosegretari […] Volevo fare un telegiornale in cui ci fosse tutto, che fosse più vicino alla gente, che fosse al servizio del pubblico non al servizio dei politici.» |

| (Enzo Biagi) |

Nel 1963 decise di dimettersi – dopo l’ultima puntata chiusa da I ragazzi di Arese di Gianni Serra – e di tornare a Milano dove divenne inviato e collaboratore dei quotidiani Corriere della Sera e La Stampa. Nel 1967 entrò nel gruppo Rizzoli come direttore editoriale. Firmava i suoi pezzi sul settimanale L’Europeo e trasformò il periodico letterario Novella in un giornale di cronaca rosa. Nel 1968 tornò alla Rai per la realizzazione di programmi di approfondimento giornalistico. Tra i più seguiti e innovativi: Dicono di lei (1969), una serie di interviste a personaggi famosi, tramite frasi, aforismi, aneddoti sulle loro personalità e Terza B, facciamo l’appello (1971), in cui personaggi famosi incontravano dei loro ex compagni di classe, amici dell’adolescenza, i primi timidi amori.

Gli anni settanta, ottanta, novanta

Nel 1971 fu nominato direttore de Il Resto del Carlino, con l’obiettivo di trasformarlo in un quotidiano nazionale. Venne data più attenzione alla cronaca e alla politica. Biagi esordì con un editoriale, che intitolò “Rischiatutto” come la celebre trasmissione di Mike Bongiorno, andata in onda su Rai 1, commentando il caos in cui si stavano svolgendo le elezioni del presidente della Repubblica (che videro poi l’elezione di Giovanni Leone) e che tennero impegnato il Parlamento per diverse settimane, concludendosi alla vigilia di Natale dopo 23 giorni.

L’editore Attilio Monti era in buoni rapporti con il ministro delle finanze Luigi Preti, che pretendeva che il giornale desse risalto alle sue attività. Biagi ignorò le richieste di Preti; poco dopo però pubblicò la sua partecipazione ad una festa al Grand Hotel di Rimini, che Preti smentì vigorosamente. La replica di Biagi (“ci dispiace che lo sbadato cronista abbia preso un abbaglio; siamo però convinti che i ministri, anche se socialisti, non hanno il dovere di vivere sotto i ponti”) mandò Preti su tutte le furie, tanto da premere per il suo allontanamento. Questo episodio, insieme all’intimazione di Monti a Biagi affinché licenziasse alcuni suoi collaboratori – tra cui il sacerdote Nazareno Fabbretti, “colpevole” di aver firmato un’intervista alla madre di don Lorenzo Milani – fu all’origine dell’uscita di Biagi dalla redazione del quotidiano bolognese. Il 30 giugno 1971 firmò il suo addio ai lettori e tornò quindi al Corriere della Sera.

Nel 1974, pur senza lasciare il Corriere, collaborò con l’amico Indro Montanelli alla creazione de Il Giornale.

Dal 1977 al 1980 Biagi ritornò a collaborare stabilmente alla Rai, conducendo Proibito, programma in prima serata su Rai 2, che trattava temi d’attualità. All’interno del programma guidò due cicli d’inchiesta internazionali denominati Douce France (1978) e Made in England (1980). Con Proibito, Biagi iniziò ad occuparsi di interviste televisive, genere di cui sarebbe divenuto un maestro. Nel programma furono intervistati, creando ogni volta scalpore e polemiche, personaggi-chiave dell’Italia dell’epoca come l’ex brigatista Alberto Franceschini, Michele Sindona, il finanziere poi coinvolto in inchieste di mafia e corruzione, e soprattutto il dittatore libico Mu’ammar Gheddafi nei giorni successivi alla caduta dell’aereo di Ustica. In quest’ultima occasione il dittatore libico sostenne che si trattava di un attentato organizzato dagli Stati Uniti contro la sua persona e che gli americani quel giorno avevano soltanto “sbagliato bersaglio”; l’intervista finì al centro di una controversia internazionale e il governo dell’epoca ne proibì la messa in onda; l’incontro fu poi regolarmente trasmesso un mese dopo.

Nel 1981, dopo lo scandalo della P2 di Licio Gelli, lasciò il Corriere della Sera, dichiarando di non essere disposto a lavorare in un giornale controllato dalla massoneria, come sembrava emergere dalle inchieste della magistratura. Come lui stesso ha rivelato, Gelli, il leader della P2, aveva chiesto all’allora direttore del quotidiano, Franco Di Bella di cacciare Biagi o di mandarlo in Argentina. Di Bella, però si rifiutò. Diventò quindi editorialista della Repubblica, dove rimase fino al 1988, quando ritornò in via Solferino.

Nel 1982 condusse la prima serie di Film Dossier, un programma che, attraverso film mirati, puntava a coinvolgere lo spettatore; nel 1983, dopo un programma su Rai 3 dedicato a episodi della seconda guerra mondiale (La guerra e dintorni), tornò su Rai 1: iniziò così a condurre Linea Diretta, uno dei suoi programmi più seguiti, che proponeva l’approfondimento del fatto della settimana, tramite il coinvolgimento dei vari protagonisti. Linea Diretta venne trasmesso fino al 1985.

Appena un anno dopo, nel 1986, sempre su Rai Uno, fu la volta di Spot, un settimanale giornalistico in quindici puntate, cui Biagi collaborava come intervistatore. In questa veste, si rese protagonista di interviste storiche come quella a Osho Rajneesh, il famoso e controverso mistico indiano, nell’anno in cui il Partito Radicale cercava di fargli ottenere il diritto di ingresso per l’Italia che gli veniva negato; oppure quella a Michail Gorbačëv, negli anni in cui il leader sovietico iniziava la perestrojka; o quella ancora a Silvio Berlusconi, nei giorni delle polemiche sui presunti favori del governo Craxi nei confronti delle sue televisioni. Berlusconi stava tentando invano di convincere Biagi ad entrare a Mediaset, ma lui rimase in RAI, sia perché legato affettivamente sia perché temeva che, nelle televisioni del Cavaliere, avrebbe avuto minore libertà.

Nel 1989 riaprì i battenti, per un anno, Linea Diretta. Questa nuova edizione verrà tra l’altro sbeffeggiata dal Trio composto da Anna Marchesini, Tullio Solenghi e Massimo Lopez, che all’epoca stava conoscendo un grande successo. In precedenza Biagi era stato imitato anche da Alighiero Noschese negli anni settanta; successivamente sarà nel mirino del Bagaglino.

Nei primi anni novanta realizzò soprattutto trasmissioni tematiche di grande spessore, come Che succede all’Est? (1990), dedicata alla fine del comunismo, I dieci comandamenti all’italiana (1991), Una storia (1992), sulla lotta alla mafia, dove apparve per la prima volta in televisione il pentito Tommaso Buscetta. Seguì attentamente le vicende dell’inchiesta Mani pulite, con programmi come Processo al processo su Tangentopoli (1993) e Le inchieste di Enzo Biagi (1993-1994). Fu il primo giornalista ad incontrare l’allora giudice Antonio Di Pietro, nei giorni in cui era considerato “l’eroe” che aveva messo in ginocchio Tangentopoli.

Il Fatto e l’«editto bulgaro»

Nel 1995 iniziò a condurre la trasmissione Il Fatto, un programma di approfondimento dopo il TG1 sui principali fatti del giorno, di cui Biagi era autore e conduttore. Nel 2004 Il Fatto fu proclamato da una giuria di critici televisivi come il miglior programma giornalistico realizzato nei primi cinquant’anni della Rai. Rilevanti furono le interviste a Marcello Mastroianni, a Sophia Loren, a Indro Montanelli e le due realizzate a Roberto Benigni.

Nel luglio del 2000, la Rai dedicò a Biagi uno speciale in occasione del suo ottantesimo compleanno, intitolato Buon compleanno signor Biagi! Ottant’anni scritti bene, condotto da Vincenzo Mollica.

La prima intervista a Benigni era stata rilasciata dopo la vittoria di quest’ultimo ai Premi Oscar del 1997, la seconda nel 2001 a ridosso delle elezioni politiche, che poi avrebbero visto la vittoria della Casa delle Libertà. In quest’ultima il comico toscano commentò, a modo suo, il conflitto di interessi e il contratto con gli italiani che Berlusconi aveva firmato qualche giorno prima nel salotto di Bruno Vespa. I commenti provocarono il giorno dopo roventi polemiche contro Biagi, che venne accusato di utilizzare la televisione pubblica per impedire la vittoria di Berlusconi. Al centro della bufera c’erano anche le dichiarazioni che il 27 marzo Indro Montanelli aveva rilasciato al Fatto. Il giornalista aveva attaccato pesantemente il centro-destra paragonandolo ad un virus per l’Italia e sostenendo che sotto Berlusconi il nostro Paese avrebbe vissuto una “dittatura morbida in cui al posto delle legioni quadrate avremmo avuto i quadrati bilanci”, ovvero molta corruzione.

In seguito a queste due interviste diversi politici e giornalisti attaccarono Biagi; tra questi Giulio Andreotti e Giuliano Ferrara che dichiarò: “Se avessi fatto a qualcuno quello che Biagi ha fatto a Berlusconi, mi sarei sputato in faccia”. La critica più dura arrivò però dal deputato di Alleanza Nazionale e futuro ministro delle comunicazioni Maurizio Gasparri, che auspicò in un’emittente lombarda l’allontanamento dalla Rai dello stesso Biagi.

Biagi fu quindi denunciato all’Autorità per le Garanzie nelle Comunicazioni per “violazione della par condicio” ma fu poi assolto con formula piena.

Il 18 aprile del 2002 l’allora presidente del Consiglio Silvio Berlusconi, mentre si trovava in visita ufficiale a Sofia, rilasciò una dichiarazione riportata dall’Agenzia Ansa e passata poi alla cronaca con la definizione giornalistica diEditto bulgaro. Berlusconi, commentando la nomina dei nuovi vertici Rai, resi pubblici il giorno prima, si augurò che “la nuova dirigenza non permettesse più un uso criminoso della televisione pubblica” come, a suo giudizio, era stato fatto dal giornalista Michele Santoro, dal comico Daniele Luttazzi e dallo stesso Biagi. Biagi replicò quella sera stessa nella puntata del Fatto, appellandosi alla libertà di stampa:

Fu l’inizio, per Enzo Biagi, di una lunga controversia fra lui e la Rai, con numerosi colpi di scena e un’interminabile serie di trattative che videro prima lo spostamento di fascia oraria del Fatto, poi il suo trasferimento su Rai 3 e infine la sua cancellazione dai palinsesti.

Biagi, sentendosi preso in giro dai vertici della Rai e credendo che non gli sarebbe mai stata affidata alcuna trasmissione, decise a settembre di non rinnovare il suo contratto con la televisione pubblica, che fu risolto dopo 41 anni di collaborazione il 31 dicembre 2002.

Nel corso del 2002 i rapporti con Berlusconi si deteriorarono sempre più a causa della pregiudiziale morale che per Biagi era imprescindibile; infatti, a tal proposito disse: «uno che fa battute come quella di Berlusconi dimostra che, nonostante si alzi i tacchi, non è all’altezza. Un presidente del Consiglio che ha conti aperti con la giustizia avrebbe dovuto avere la decenza di sbrigare prima le sue pratiche legali e poi proporsi come guida del Paese. (Il Fatto, 8 aprile 2002)»

Nel novembre dello stesso 2002 divenne uno dei fondatori e garanti dell’associazione culturale Libertà e Giustizia, spesso critica verso l’operato dei governi guidati da Berlusconi.

Gli ultimi anni: il ritorno in televisione

In questo stesso periodo, Biagi fu colpito da due gravi lutti: la morte della moglie Lucia il 24 febbraio 2002 e della figlia Anna il 28 maggio 2003, cui era legatissimo, scomparsa improvvisamente per un arresto cardiaco. Questa morte lo segnò per il resto della sua vita.

Continuò a criticare aspramente il governo Berlusconi, dalle colonne del Corriere della Sera. L’atto più clamoroso fu quando (in seguito al famoso episodio di Berlusconi che con il dito medio alzato durante un comizio a Bolzanoespresse che cosa pensava dei suoi critici) chiese “scusa, a nome del popolo italiano, perché il nostro presidente del Consiglio non ha ancora capito che è un leader di una democrazia”. Berlusconi replicò dichiarandosi stupito che “il Corriere della Sera pubblicasse i racconti di un vecchio rancoroso come Biagi”. Il comitato di redazione del Corriere protestò con una lettera aperta indirizzata a Berlusconi, dicendosi orgoglioso che un giornalista come Biagi lavorasse nel suo quotidiano e sostenendo che “in Via Solferino lavorano dei giornalisti non dei servi”.

Tornò in televisione, dopo due anni di silenzio, alla trasmissione Che tempo che fa, intervistato per una ventina di minuti da Fabio Fazio. Il suo ritorno in televisione registrò ascolti record per Rai 3 e per la stessa trasmissione di Fazio.

Biagi tornò poi altre due volte alla trasmissione di Fazio, testimoniando ogni volta il suo affetto per la Rai («la mia casa per quarant’anni») e la sua particolare vicinanza a Rai 3.

Biagi intervenne anche al Tg3 e in altri programmi della Rai. Invitato anche da Adriano Celentano nel suo Rockpolitik, in onda su Rai 1, in una puntata dedicata alla libertà di stampa assieme a Santoro e Luttazzi, Biagi declinò l’invito per il fatto che nella rete ammiraglia della Rai c’era la presenza delle persone che avevano chiuso il suo programma; tra queste persone sarebbe stato compreso anche l’allora direttore Fabrizio Del Noce.

Negli ultimi anni scrisse anche con il settimanale L’Espresso e le riviste Oggi e TV Sorrisi e Canzoni.

Nell’agosto del 2006, intervenendo su il Tirreno, avanzò delle perplessità circa la sentenza di primo grado emessa dagli organi di giustizia sportiva in relazione allo scandalo che colpì il calcio italiano a partire dal maggio dello stesso anno e noto giornalisticamente come Calciopoli.

Nella sua ultima intervista a Che tempo che fa, nell’autunno del 2006 Biagi affermò che il suo ritorno in Rai era molto vicino e, al termine della trasmissione, il direttore generale della Rai, Claudio Cappon, telefonando in diretta, annunciava che l’indomani stesso Biagi avrebbe firmato il contratto che lo riportava in TV.

Il 22 aprile 2007 tornò in televisione con RT Rotocalco Televisivo, aprendo la trasmissione con queste parole:

| «Buonasera, scusate se sono un po’ commosso e magari si vede. C’è stato qualche inconveniente tecnico e l’intervallo è durato cinque anni. C’eravamo persi di vista, c’era attorno a me la nebbia della politica e qualcuno ci soffiava dentro… Vi confesso che sono molto felice di ritrovarvi. Dall’ultima volta che ci siamo visti, sono accadute molte cose. Per fortuna, qualcuna è anche finita.» |

| (Editoriale dal sito ufficiale della trasmissione) |

Essendo alla vigilia della festa del 25 aprile, l’argomento della puntata fu la resistenza, sia in senso moderno, come di chi resiste alla camorra, fino alla Resistenza storica, con interviste a chi l’ha vissuta in prima persona.

La trasmissione andò in onda per sette puntate, oltre allo speciale iniziale, fino all’11 giugno 2007. Sarebbe dovuta riprendere nell’autunno successivo. Ciò non avvenne a causa dell’improvviso aggravarsi delle condizioni di salute di Biagi.

La morte

Ricoverato per oltre dieci giorni in una clinica milanese, a causa di un edema polmonare acuto e di sopraggiunti problemi renali e cardiaci, Enzo Biagi morì all’età di 87 anni la mattina del 6 novembre 2007. Pochi giorni prima di morire, disse a un’infermiera «Si sta come d’autunno sugli alberi le foglie…», ricordando Soldati di Ungaretti, e aggiungendo «ma tira un forte vento».

I funerali del giornalista si svolsero nella chiesa del piccolo borgo natale di Pianaccio, vicino a Lizzano in Belvedere, e la sepoltura avvenne nel piccolo cimitero poco distante. La messa esequiale venne officiata dal cardinaleErsilio Tonini, suo vecchio amico, alla presenza del presidente del Consiglio Romano Prodi, dei vertici Rai e di molti colleghi, come Ferruccio de Bortoli e Paolo Mieli.

Nei giorni precedenti era stata aperta a Milano la camera ardente che vide una partecipazione popolare immensa, definita “stupefacente” dalle sue stesse figlie. Alle redazioni dei giornali e ai familiari arrivarono lettere di cordoglio e di condoglianze da ogni parte d’Italia, anche la maggioranza dei principali siti Internet e molti blog lo ricordarono con parole affettuose, segno della grande commozione che la sua scomparsa aveva provocato.

Successivamente furono molte le iniziative per ricordarlo. Michele Santoro gli dedicò una puntata nella sua trasmissione Annozero titolata “Biagi, partigiano sempre”; Blob e Speciale TG1 riproposero i filmati dei suoi programmi più significativi; il Corriere della Sera organizzò una serata commemorativa presso la Sala Montanelli, la Rai invece lo onorò con una serata presso il teatro Quirino a Roma trasmessa in diretta su Rai News 24 e poi in replica su Rai Tre in seconda serata.

POSTE ITALIANE 28th issue on 09 August 2020 of a commemorative stamp of Enzo Biagi, on the centenary of his birth

Poste Italiane announces that today 9 August 2020 a commemorative stamp of Enzo Biagi, on the centenary of his birth, will be issued by the Ministry of Economic Development, relating to the value of tariff B equal to € 1.10.

- date 09 agosto 2020

- indentation 11

- print gravure printing

- type of paper neutral coated white paper – self-adhesive

- printed I.P.Z.S. Roma

- edition 400.000

- dimensions 40 x 30 mm

- value B= €1.10

- sketcher by the Philatelic Center of the Operations Management of the State Printing and Mint Institute S.p.A ..

- num. catalog Michel YT UN

If you are interested in purchasing this stamp, you can buy it for € 1.50. Send me a request to the email: protofilia1@gmail.com

Enzo Marco Biagi (Pianaccio di Lizzano in Belvedere, 9 August 1920 – Milan, 6 November 2007) was an Italian journalist, writer, TV presenter and partisan. He was one of the most popular faces of 20th century Italian journalism.

Biography

The beginnings

Born in the small Apennine village of Pianaccio, at the age of nine he moved to Bologna in the district of Porta Sant’Isaia, where his father Dario (1891-1942) had already worked for some years as deputy warehouse manager in a sugar factory. The idea of becoming a journalist was born in him after reading Jack London’s Martin Eden. He attended the technical institute for accountants Pier Crescenzi, where with other companions he gave life to a small student magazine, Il Picchio, which mainly dealt with school life. The Picchio was suppressed after a few months by the fascist regime and since then a strong anti-fascist nature was born in Biagi. In 1937, at the age of seventeen, he began to collaborate with the Bolognese daily L’Avvenire d’Italia, dealing with news, color and small interviews with opera singers. His first article was dedicated to the dilemma, alive in the criticism of the time, whether the Cesenatico poet Marino Moretti was crepuscular or not. In 1940 he was hired on a permanent basis by Carlino Sera, the afternoon edition of Resto del Carlino, the main Bolognese newspaper, as a news writer, that is the one who deals with arranging the articles brought to the editorial office (the work of “kitchen”, as he says in jargon). In 1942 he was called to arms but did not leave for the front due to heart problems (which will accompany him throughout his life). On 18 December 1943 he married Lucia Ghetti, a primary school teacher. Shortly after, he was forced to take refuge in the mountains, where he joined the Resistance fighting in the Justice and Freedom brigades linked to the Action Party, whose program and ideals he shared. In reality, Biagi never fought: his commander, in fact, even without doubting his fidelity, found him too frail. First he gave him relay duties, then entrusted him with the drafting of a partisan newspaper, Patrioti, of which Biagi was practically the only editor and with which he informed the people about the real course of the war along the Gothic Line. Only four issues of the newspaper came out: the printing house was destroyed by the Germans. Biagi always considered the months he spent as a partisan as the most important of his life: in memory of this, he wanted his body to be accompanied to the cemetery on the notes of Bella ciao. After the war, Biagi entered with the allied troops in Bologna and it was he who announced the liberation from the microphones of the allied Psychological Warfare Branch. Shortly after, he was hired as a special correspondent and film critic at the Resto del Carlino, which at the time had changed its name to Giornale dell’Emilia. In 1946 he followed the Giro d’Italia as a special envoy, in 1947 he left for Great Britain where he told the wedding of the future Queen Elizabeth II. It was the first of a long series of trips abroad as a “witness of the time” that will mark his entire life.

The fifties and sixties

The first direction: Epoca

In 1951 he went, on behalf of Carlino, to Polesine where, with a chronicle that has remained in the annals, he described the flood that plagued the province of Rovigo; despite the great success that those articles had, Biagi was isolated within the newspaper due to some of his statements against the atomic bomb, which made him pass for a communist and which made him consider, therefore, a “dangerous subversive” for the its director. However, the articles on Polesine were also read by Bruno Fallaci, editor of the weekly Epoca, in search of new elements for his editorial offices. Fallaci called him to work as editor in chief at the periodical. Biagi and his family (two daughters had already been born, Bice and Carla; Anna will arrive in 1956) then left their beloved Bologna for Milan. In 1952 Epoca was going through a difficult time. In search of exclusive scoops to be able to publish in Italy, the new director Renzo Segala, who took over from Bruno Fallaci for a month, decided to leave for America, entrusting Biagi with the leadership of the newspaper for two weeks, establishing the themes to be to face during his absence, namely the return of Trieste to Italy and the beginning of spring. In the meantime, however, the “Wilma Montesi case” broke out: a young Roman girl was found dead on the beach of Ostia; a scandal was born in which the upper middle class of Lazio, the prefect of Rome and Piero Piccioni, son of the minister Attilio Piccioni, were involved, who resigned. Biagi, sensing the great resonance that the Montesi case was having in the country, decided, against all regulations, to dedicate the cover to it and to publish an unprecedented reconstruction of the facts. It was a resounding success: the circulation of Epoca grew by over twenty thousand copies in a single week and Mondadori took the direction from Segàla, who had recently returned from the United States, entrusting it to Biagi. Under the direction of Biagi, Epoca established itself in the panorama of the great Italian magazines, outclassing the historical competition of l’Espresso and del’Europeo. The Epoca formula, innovative at that time, aims to recount the news of the week and the stories of Italy in the boom with summaries and insights. Another exclusive scoop will be the publication of photographs depicting a very human Pope Pius XII playing with a canary. In 1960 an article on the clashes in Genoa and Reggio Emilia against the Tambroni government (which had caused the death of ten workers on strike, so much so that it was defined as the Reggio Emilia massacre) provoked a harsh reaction from the same government, for which Biagi was forced to leave Epoca. A few months later he was hired by the Press as a special envoy.

The arrival on Rai: the news

On 1 October 1961 he became director of the newscast. Biagi immediately set to work, applying the Epoca formula to the news, giving less space to politics and more to the “troubles of the Italians”, as he called the shortcomings of our system. He carried out a memorable interview with Salvatore Gallo, the life imprisoner unjustly imprisoned in Ventotene, whose story will later lead the Parliament to approve the review of the trials even after the cassation sentence. He devoted services to the Soviet Union’s nuclear tests that had sown panic across Europe. He hired great journalists like Giorgio Bocca and Indro Montanelli for Rai, but also young people like Enzo Bettiza and Emilio Fede, destined for a long career.

In November 1961 the first controversies inevitably arrived: the Christian Democrat Guido Gonella, in a parliamentary question to the Minister of the Interior Mario Scelba – then went down in history for the attacks on the bare legs of the Kessler twins, – accused Enzo Biagi of being biased and to “not be aligned with the official”. A prime-time interview with Communist leader Palmiro Togliatti got him a severe attack from right-wing newspapers, which start an aggressive campaign against him.

In March 1962 he launched the first television rotogravure of Italian television: RT Rotocalco Televisivo. It first appeared on video; the shy Biagi will always remember his first recordings as a torment. He conducted the broadcast until 1968. In Rome, however, Biagi felt his hands were tied. The political pressures were persistent; Biagi had already said no to Giuseppe Saragat, who offered him some services, but resisting was difficult despite the public solidarity that came to him from famous personalities of the period such as Giovannino Guareschi, Garinei and Giovannini, Giangiacomo Feltrinelli, Liala and by Bernabei himself.

“I was the wrong man in the wrong place: I didn’t know how to keep political equilibrium, in fact they just didn’t interest me and I didn’t like being on the phone with ladies and undersecretaries […] I wanted to make a newscast in which there was everything, that it was more close to the people, who was in the service of the public not in the service of politicians. “

(Enzo Biagi)

In 1963 he decided to resign – after the last episode closed by Gianni Serra’s I Ragazzi di Arese – and to return to Milan where he became a correspondent and collaborator of the newspapers Corriere della Sera and La Stampa. In 1967 he joined the Rizzoli group as editorial director. He signed his pieces in the weekly L’Europeo and transformed the literary periodical Novella into a gossip newspaper. In 1968 he returned to Rai for the production of journalistic in-depth programs. Among the most followed and innovative: Dicono di lei (1969), a series of interviews with famous people, through phrases, aphorisms, anecdotes about their personalities and Terza B, let’s make an appeal (1971), in which famous people met their former classmates, friends of adolescence, the first timid loves.

The seventies, eighties, nineties

In 1971 he was appointed director of Il Resto del Carlino, with the aim of turning it into a national newspaper. More attention was given to news and politics. Biagi began with an editorial, which he titled “Rischiatutto” after the famous show by Mike Bongiorno, aired on Rai 1, commenting on the chaos in which the elections for the President of the Republic were taking place (which later saw the election of Giovanni Leone ) and that kept Parliament busy for several weeks, ending on Christmas Eve after 23 days.

The publisher Attilio Monti was on good terms with the finance minister Luigi Preti, who wanted the newspaper to highlight his activities. Biagi ignored Preti’s requests; shortly after, however, he published his participation in a party at the Grand Hotel in Rimini, which Preti vigorously denied. Biagi’s reply (“we are sorry that the careless reporter made a mistake; however we are convinced that the ministers, even if socialists, do not have the duty to live under bridges”) sent Preti into a rage, so much so that his removal. This episode, together with Monti’s ordering Biagi to dismiss some of his collaborators – including the priest Nazareno Fabbretti, “guilty” of having signed an interview with Don Lorenzo Milani’s mother – was at the origin of Biagi’s exit from editing of the Bolognese newspaper. On June 30, 1971, he signed his farewell to readers and then returned to Corriere della Sera.

In 1974, without leaving the Corriere, he collaborated with his friend Indro Montanelli on the creation of Il Giornale.

From 1977 to 1980 Biagi returned to collaborate permanently with Rai, conducting Proibito, a prime-time program on Rai 2, which dealt with current affairs. Within the program he led two international rounds of inquiries called Douce France (1978) and Made in England (1980). With Proibito, Biagi began to deal with television interviews, a genre of which he would become a master. In the program, key figures of the Italy of the time were interviewed, each time creating a stir and controversy, such as the former Brigadier Alberto Franceschini, Michele Sindona, the financier later involved in mafia and corruption investigations, and above all the Libyan dictator Mu ‘ ammar Gaddafi in the days following the crash of the Ustica plane. On this last occasion, the Libyan dictator argued that it was an attack organized by the United States against him and that the Americans had only “the wrong target” that day; the interview ended up at the center of an international controversy and the government of the time forbade its broadcasting; the m In 1981, after the scandal of Licio Gelli’s P2, he left Corriere della Sera, declaring that he was unwilling to work in a newspaper controlled by the Freemasonry, as seemed to emerge from the investigations of the judiciary. As he himself revealed, Gelli, the leader of P2, had asked the then director of the newspaper, Franco Di Bella, to kick Biagi out or send him to Argentina. Di Bella, however, refused. He then became a columnist for the Republic, where he remained until 1988, when he returned to via Solferino.

In 1982 he conducted the first series of Film Dossier, a program which, through targeted films, aimed to involve the viewer; in 1983, after a program on Rai 3 dedicated to episodes of the Second World War (La guerra e dintorni), he returned to Rai 1: he thus began conducting Linea Diretta, one of his most popular programs, which proposed an in-depth study of the fact of week, through the involvement of the various protagonists. Direct Line was broadcast until 1985.

Just a year later, in 1986, again on Rai Uno, it was the turn of Spot, a journalistic weekly in fifteen episodes, in which Biagi collaborated as an interviewer. In this capacity, he became the protagonist of historical interviews such as the one with Osho Rajneesh, the famous and controversial Indian mystic, in the year in which the Radical Party tried to get him the right of entry to Italy that was denied him; or that to Mikhail Gorbachev, in the years in which the Soviet leader began perestroika; or the one still to Silvio Berlusconi, in the days of the controversy over the alleged favors of the Craxi government towards its televisions. Berlusconi was trying in vain to convince Biagi to join Mediaset, but he remained in RAI, both because he was emotionally tied and because he feared that, on the Cavaliere’s televisions, he would have less freedom.

In 1989, Linea Diretta reopened its doors for a year. This new edition will be mocked among other things by the Trio composed of Anna Marchesini, Tullio Solenghi and Massimo Lopez, who at the time was enjoying great success. Previously Biagi had also been imitated by Alighiero Noschese in the seventies; subsequently it will be in the Bagaglino’s sights.

In the early nineties he mainly produced thematic broadcasts of great depth, such as What happens in the East? (1990), dedicated to the end of communism, The Ten Commandments in the Italian style (1991), Una storia (1992), on the fight against the Mafia, where the repentant Tommaso Buscetta appeared for the first time on television. He closely followed the events of the Clean Hands investigation, with programs such as Trial Process on Tangentopoli (1993) and Enzo Biagi’s Investigations (1993-1994). He was the first journalist to meet the then judge Antonio Di Pietro, in the days when he was considered “the hero” who had brought Tangentopoli to its knees.

The Fact and the “Bulgarian Edict”

In 1995 he began to conduct the broadcast Il Fatto, an in-depth program after TG1 on the main events of the day, of which Biagi was the author and host. In 2004 Il Fatto was proclaimed by a jury of television critics as the best journalistic program produced in Rai’s first fifty years. The interviews with Marcello Mastroianni, Sophia Loren, Indro Montanelli and the two made with Roberto Benigni were relevant.

In July 2000, Rai dedicated a special to Biagi on the occasion of his eightieth birthday, entitled Happy birthday Mr. Biagi! Eighty years written well, conducted by Vincenzo Mollica.

The first interview with Benigni was released after the latter’s victory at the 1997 Oscar Awards, the second in 2001 close to the political elections, which would then have seen the victory of the House of Liberty. In the latter, the Tuscan comedian commented, in his own way, on the conflict of interests and the contract with the Italians that Berlusconi had signed a few days earlier in Bruno Vespa’s living room. The comments provoked heated controversy the next day against Biagi, who was accused of using public television to prevent Berlusconi’s victory. At the center of the storm were also the declarations that Indro Montanelli had made to the Fact on 27 March. The journalist had heavily attacked the center-right comparing it to a virus for Italy and arguing that under Berlusconi our country would have experienced a “soft dictatorship in which, instead of the square legions, we would have had square budgets”, that is, a lot of corruption.eeting was then regularly broadcast a month later. Following these two interviews, several politicians and journalists attacked Biagi; among these Giulio Andreotti and Giuliano Ferrara who declared: “If I had done to someone what Biagi did to Berlusconi, I would have spit in my face”. The harshest criticism, however, came from the deputy of the National Alliance and future communications minister Maurizio Gasparri, who hoped that Biagi himself would be removed from Rai by a Lombard broadcaster. Biagi was then reported to the Communications Authority for “violation of the level playing field” but was later acquitted with full formula.

On April 18, 2002, the then Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi, while on an official visit to Sofia, released a statement reported by the Ansa Agency and then passed to the news with the journalistic definition of Bulgarian Edict. Berlusconi, commenting on the appointment of the new RAI leaders, made public the day before, hoped that “the new leadership would no longer allow a criminal use of public television” as, in his opinion, had been done by the journalist Michele Santoro, by the comedian Daniele Luttazzi and by Biagi himself. Biagi replied that same evening in the episode of the Fact, appealing to the freedom of the press.

It was the beginning, for Enzo Biagi, of a long dispute between him and Rai, with numerous twists and an interminable series of negotiations that saw first the shift of the time slot of the Fact, then its transfer to Rai 3 and finally, its cancellation from the schedules.

Biagi, feeling teased by the top management of Rai and believing that he would never be entrusted with any broadcast, decided in September not to renew his contract with public television, which was terminated after 41 years of collaboration on 31 December 2002.

During 2002, relations with Berlusconi deteriorated more and more due to the moral prejudice that for Biagi was essential; in fact, in this regard he said: «someone who makes jokes like Berlusconi’s shows that, despite raising his heels, he is not up to par. A prime minister who has open accounts with justice should have had the decency to first deal with his legal procedures and then propose himself as the country’s guide. (Il Fatto, April 8, 2002) “

In November 2002 he became one of the founders and guarantors of the cultural association Libertà e Giustizia, often critical of the work of governments led by Berlusconi.

The last few years: the return to television

In this same period, Biagi was struck by two serious mourning: the death of his wife Lucia on February 24, 2002 and of his daughter Anna on May 28, 2003, to whom he was very close, who suddenly died of cardiac arrest. [15] This death marked him for the rest of his life.

He continued to harshly criticize the Berlusconi government, from the columns of the Corriere della Sera. The most sensational act was when (following the famous episode of Berlusconi who, with his middle finger raised during a rally in Bolzano, expressed what he thought of his critics) he asked “sorry, on behalf of the Italian people, because our Prime Minister he has not yet understood that he is a leader of a democracy “. Berlusconi replied declaring himself amazed that “the Corriere della Sera published the stories of a rancorous old man like Biagi”. The editorial board of the Corriere protested with an open letter addressed to Berlusconi, saying he was proud that a journalist like Biagi worked in his newspaper and arguing that “in Via Solferino there are journalists, not servants”.

He returned to television, after two years of silence, at the show Che tempo che fa, interviewed for about twenty minutes by Fabio Fazio. His return to television recorded record ratings for Rai 3 and for the same broadcast by Fazio. Biagi then returned two more times to Fazio’s broadcast, each time testifying his affection for Rai (“my home for forty years”) and his particular closeness to Rai 3.

Biagi also took part in Tg3 and in other Rai programs. Also invited by Adriano Celentano in his Rockpolitik, broadcast on Rai 1, in an episode dedicated to freedom of the press together with Santoro and Luttazzi, Biagi declined the invitation due to the fact that in the Rai flagship network there was the presence of people that they had closed his program; among these people was also included the then director Fabrizio Del Noce.

In recent years he has also written with the weekly L’Espresso and the magazines Oggi and TV Sorrisi e Canzoni.

In August 2006, intervening on the Tyrrhenian Sea, he raised some doubts about the first instance sentence issued by the sports justice bodies in relation to the scandal that hit Italian football starting from May of the same year and known journalistically as Calciopoli.

In his last interview with Che tempo che fa, in the autumn of 2006 Biagi stated that his return to Rai was very close and, at the end of the broadcast, the director general of Rai, Claudio Cappon, calling live, announced that the tomorrow Biagi himself would sign the contract that brought him back to TV.

On 22 April 2007 he returned to television with RT Rotocalco Televisivo, opening the broadcast with these words:

«Good evening, sorry if I’m a little moved and maybe it shows. There were some technical hiccups and the interval lasted five years. We had lost sight of each other, the fog of politics was around me and someone was blowing into it… I confess that I am very happy to see you again. A lot has happened since we last met. Fortunately, some of them are also over. “

(Editorial from the official website of the broadcast)

Being on the eve of the feast of April 25th, the topic of the episode was resistance, both in the modern sense, as of those who resist the Camorra, up to the historical Resistance, with interviews with those who lived it firsthand.

The broadcast aired for seven episodes, in addition to the initial special, until June 11, 2007. It was due to resume in the following fall. This did not happen due to the sudden worsening of Biagi’s health conditions.

The death

Hospitalized for over ten days in a Milanese clinic, due to acute pulmonary edema and kidney and heart problems, Enzo Biagi died at the age of 87 on the morning of November 6, 2007. A few days before he died, he told a ‘nurse “The leaves are like autumn on the trees …”, recalling Soldati by Ungaretti, and adding “but there is a strong wind”. The journalist’s funeral took place in the church of the small hometown of Pianaccio, near Lizzano in Belvedere, and the burial took place in the small cemetery not far away. The funeral mass was officiated by Cardinal Ersilio Tonini, his old friend, in the presence of the Prime Minister Romano Prodi, the RAI leaders and many colleagues, such as Ferruccio de Bortoli and Paolo Mieli.

In the previous days the funeral parlor had been opened in Milan which saw an immense popular participation, defined as “amazing” by her own daughters. Letters of condolence and condolences arrived from all over Italy to the newspaper editors and family members, even the majority of the main Internet sites and many blogs remembered him with affectionate words, a sign of the great emotion that his death had caused.

Subsequently there were many initiatives to remember him. Michele Santoro dedicated an episode to him in his Annozero program entitled “Biagi, always a partisan”; Blob and Speciale TG1 reproposed the videos of his most significant programs; Corriere della Sera organized a commemorative evening at the Sala Montanelli, while Rai honored him with an evening at the Quirino theater in Rome, broadcast live on Rai News 24 and then replicated on Rai Tre in the late evening.