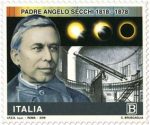

POSTE ITALIANE 17^ Emissione del 28 giugno 2018

Titolo: 200° Anniversario della nascita di Padre Angelo Secchi

Angelo Secchi nacque a Reggio Emilia il 28 giugno 1818 (alcuni biografi riportano il giorno 29) da Giacomo Antonio e Luigia Belgieri, ultimo di una famiglia numerosa, di modesta estrazione sociale e con salde radici cristiane. Ancor giovanissimo, rimase orfano di padre; la madre, che gli era molto legata, volle che ricevesse un’istruzione di buon livello ed all’età di 10 anni Secchi entrò nel Collegio dei Padri gesuiti di Reggio dove studiò lettere classiche, distinguendosi per le sue qualità intellettuali e per l’amore allo studio, nonché per il carattere «grave ed assennato». Il 3 novembre 1833, all’età di quindici anni, fu ammesso nel noviziato della Compagnia di Gesù a s. Andrea al Quirinale in Roma. Al termine del noviziato rimase altri due anni a s. Andrea per studiare retorica, poi nel 1837 iniziò gli studi di Filosofia al Collegio Romano. Qui mostrò una speciale inclinazione per le scienze, in particolare per la matematica e la fisica; in queste discipline ebbe come professori, rispettivamente, Francesco De Vico, direttore dell’Osservatorio del Collegio, e Giovan Battista Pianciani. Dopo un anno trascorso al Collegio dei Nobili a Roma ad insegnare grammatica, su richiesta di Pianciani fu trasferito al Collegio Illirico di Loreto, dove insegnò fisica dal 1841 al 1844. Tornò quindi al Collegio Romano per intraprendere lo studio della Teologia, assumendo allo stesso tempo l’incarico di assistente di Pianciani. Al termine del terzo anno degli studi teologici, ricevette l’ordinazione sacerdotale il 12 agosto 1847. La sua formazione fu però bruscamente interrotta a causa delle vicende politiche di quel periodo. L’Italia si trovava all’epoca in pieno fermento risorgimentale. I moti rivoluzionari del 1848 portarono, tra l’altro, allo scioglimento ed all’esilio volontario della Compagnia di Gesù. Secchi si trovò quindi costretto, con i suoi confratelli, a lasciare l’Italia. Trovò ospitalità per sei mesi nel Collegio di Stonyhurst in Inghilterra, dove studiò privatamente matematica superiore ed inglese; poi, nell’ottobre dello stesso anno, con un gruppo di confratelli salpò da Liverpool per raggiungere gli Stati Uniti, dirigendosi quindi al Collegio di Georgetown a Washington, dove aveva trovato accoglienza il suo maestro Francesco De Vico e dove più volte gli era stato chiesto di recarsi per insegnare fisica e matematica.

A Georgetown strinse amicizia con il padre gesuita James Curley, direttore dell’Osservatorio Astronomico del Collegio; all’epoca, tuttavia, Secchi non si occupava ancora di astronomia ma principalmente di fisica. È a questo periodo che risalgono le sue prime pubblicazioni scientifiche, in particolare gli studi sulla reometria elettrica. Il suo soggiorno negli Stati Uniti fu di grande importanza per la sua formazione, poiché ebbe l’occasione di entrare in contatto con un ambiente scientifico vivace e innovativo e di apprendere le teorie più moderne nel campo della fisica e della meteorologia. Alla fine del 1849, con la caduta della Repubblica Romana, i Gesuiti fecero rientro a Roma e Secchi fu chiamato ad assumere la direzione dell’Osservatorio del Collegio Romano, succedendo così al suo maestro Francesco De Vico. Una volta incaricato della direzione dell’Osservatorio, Secchi si preoccupò, innanzi tutto, di rinnovarne la strumentazione. Grazie alla somma lasciata in eredità dai familiari al suo assistente Paolo Rosa e messa a disposizione dell’Osservatorio, Secchi acquistò un telescopio equatoriale Merz di 22 cm di apertura, uno dei più grandi allora esistenti in Italia, col quale iniziò le sue ricerche astronomiche. Nel 1853 iniziò la pubblicazione delle Memorie dell’Osservatorio del Collegio Romano, dove sono raccolti i risultati delle sue ricerche. Nel 1863 iniziò lo studio degli spettri stellari che lo porterà ad una delle prime classificazioni delle stelle per tipi spettrali, lavoro pionieristico che costituirà il punto di partenza delle principali classificazioni eseguite negli Stati Uniti sul finire del secolo. Nel 1867 Secchi ottenne da Pio IX i fondi per la costruzione di un meteorografo, strumento da lui progettato per la registrazione giornaliera dei dati meteorologici, da presentare all’Esposizione Universale di Parigi; qui lo strumento ottenne l’attribuzione del Grand Prix, mentre lo stesso Secchi ricevette la Legion d’Onore dall’imperatore di Francia Napoleone III e l’Ordine della Rosa dall’imperatore del Brasile Pedro II: la sua carriera scientifica giungeva così al culmine.

Con la presa di Roma nel 1870, iniziò per Secchi un periodo di grandi difficoltà. Scienziato di fama ormai mondiale, egli divenne un personaggio scomodo nell’ambito dei rapporti allora conflittuali tra Governo italiano e Stato Pontificio.

Subentrato all’autorità papale, il Governo unitario, su pressione della comunità scientifica internazionale, lasciò Secchi alla direzione dell’Osservatorio del Collegio Romano, accettando le condizioni da lui poste d’intesa con i suoi superiori. Il Governo gli propose anche la cattedra universitaria di Astronomia fisica all’Università La Sapienza , che Secchi in un primo momento accettò ma alla quale fu poi costretto a rinunciare per motivi esclusivamente politici, legati alla libertà d’insegnamento dei Gesuiti nelle scuole. In quello stesso anno, Secchi pubblicava la prima edizione del celebre trattato Le Soleil (1870), uno dei più importanti testi di astronomia solare dell’Ottocento.

Ma la situazione precipitò nel 1873, con la confisca dei beni ecclesiastici e il conseguente passaggio del Collegio Romano sotto le dipendenze del Governo italiano. Secchi tentò con ogni mezzo legale di difendere l’Osservatorio, nel quale aveva investito denari ed energie, chiedendo che fosse riconosciuto come Osservatorio Pontificio e quindi tutelato dalla legge sulle Guarentigie. In prima battuta egli ottenne che i locali dell’Osservatorio fossero isolati dal resto dell’edificio, mantenendo l’accesso per sé e per i suoi collaboratori.

Nel 1875 partecipò al Congresso degli Scienziati Italiani a Palermo e fu invitato in quella circostanza a far parte della Commissione governativa istituita per pianificare il servizio meteorologico nazionale. Questa propose al Governo l’istituzione di un Ufficio Centrale e di un Consiglio Direttivo per la Meteorologia per il coordinamento dei servizi meteorologici nazionali; il Consiglio fu istituito nel novembre del 1876 e nel marzo 1877 Secchi ne fu eletto Presidente.

La sua salute, intanto, sempre piuttosto malferma, andava deteriorandosi; egli aveva dovuto progressivamente abbandonare l’attività di ricerca, dedicandosi sempre più alla stesura di opere e trattati. Nel 1875 pubblicò il primo volume della seconda edizione de Le Soleil e nel 1877 seguì il secondo volume ed il trattato Le stelle. Saggio di Astronomia Siderale. Si preparava la pubblicazione delle sue Lezioni di Fisica Terrestre (uscito poi postumo nel 1879) quando, nell’agosto del 1877 si manifestarono i primi sintomi di un cancro allo stomaco che nel giro di pochi mesi ebbe ragione delle sue forze. Dietro indicazione dei medici, nel tentativo di trovare giovamento alle sue sofferenze, alla fine di novembre di quello stesso anno si recò presso la Villa s. Girolamo a Fiesole. Non ne ricavò tuttavia alcun miglioramento e, sentendo aggravarsi il suo stato di salute, alla fine del mese di dicembre fece ritorno al Collegio Romano. Sopportò con dignità e rassegnazione gli ultimi difficili mesi di malattia, spegnendosi il 26 febbraio 1878, all’età di 59 anni.

Le convinzioni sul rapporto fra scienza e fede

Angelo Secchi rappresenta il punto d’incontro tra lo scienziato appassionato e l’uomo di fede convinto e aperto al dialogo: nei suoi scritti mai emergono punte di fanatismo o di clericalismo. Ciò che più colpisce in lui è la fedeltà alla Chiesa ed il grande amore alla verità, tenacemente perseguita con i mezzi della scienza e coi princìpi della fede. Vissuto in un’epoca non facile per i rapporti tra Stato e Chiesa, oltre che tra scienza e fede, egli diede una singolare testimonianza di solida coerenza di fede vissuta e di scienziato intelligente e profondo, dalle soluzioni innovative e, in certo modo fondative per l’astronomia del suo tempo. Egli seppe sostenere non poche difficoltà, incomprensioni ed amarezze, ma lo fece sempre con un grande senso di professionalità e con carità cristiana.

Title: 200th Anniversary of the birth of Father Angelo Secchi

Angelo Secchi was born in Reggio Emilia on June 28, 1818 (some biographers report on the 29th) by Giacomo Antonio and Luigia Belgieri, last of a large family, of modest social background and with firm Christian roots. Still very young, he remained an orphan of a father; his mother, who was very close to him, wanted him to receive a good education and at the age of 10 years Secchi entered the College of the Jesuit Fathers of Reggio where he studied classical letters, distinguishing himself for his intellectual qualities and love to the study, as well as for the ‘serious and sensible’ nature. On November 3, 1833, at the age of fifteen, he was admitted into the novitiate of the Society of Jesus at s. Andrea al Quirinale in Rome. At the end of the novitiate it remained another two years in s. Andrea to study rhetoric, then in 1837 he began his studies in Philosophy at the Roman College. Here he showed a special inclination for the sciences, especially for mathematics and physics; in these disciplines he had as professors, respectively, Francesco De Vico, director of the Observatory of the College, and Giovan Battista Pianciani. After a year spent at the Collegio dei Nobili in Rome to teach grammar, at the request of Pianciani he was transferred to the Illyricum College of Loreto, where he taught physics from 1841 to 1844. He then returned to the Roman College to undertake the study of theology, assuming at the same time Pianciani’s assistant position. At the end of the third year of theological studies, he received priestly ordination on 12 August 1847. His formation was abruptly interrupted because of the political events of that period. Italy was at the time in full swing of the Risorgimento. The revolutionary revolts of 1848 led, among other things, to the dissolution and voluntary exile of the Society of Jesus. Secchi therefore found himself forced, with his brothers, to leave Italy. He found hospitality for six months in the College of Stonyhurst in England, where he privately studied higher mathematics and English; then, in October of the same year, with a group of confreres he sailed from Liverpool to reach the United States, then heading to the Georgetown College in Washington, where his teacher Francesco De Vico had been welcomed and where he had been asked several times. to go to teach physics and mathematics.

In Georgetown he became friends with his Jesuit father James Curley, director of the College Astronomical Observatory; at the time, however, Secchi did not deal with astronomy but mainly with physics. His first scientific publications date back to this period, in particular the studies on electrical rheometry. His stay in the United States was of great importance for his training, as he had the opportunity to get in touch with a lively and innovative scientific environment and to learn the most modern theories in the field of physics and meteorology. At the end of 1849, with the fall of the Roman Republic, the Jesuits returned to Rome and Secchi was called to assume the direction of the Osservatorio del Collegio Romano, thus succeeding his teacher Francesco De Vico. Once he was in charge of the Observatory’s management, Secchi worried, first of all, to renew the instrumentation. Thanks to the sum inherited by his family to his assistant Paolo Rosa and made available to the Observatory, Secchi bought a Merz equatorial telescope of 22 cm opening, one of the largest then existing in Italy, with which he began his astronomical research. In 1853 he began the publication of the Memories of the Observatory of the Collegio Romano, where the results of his research are collected. In 1863 he began the study of stellar spectra that will lead him to one of the first classifications of stars for spectral types, pioneering work that will constitute the starting point of the main classifications carried out in the United States at the end of the century. In 1867 Secchi obtained from Pius IX the funds for the construction of a meteorographer, an instrument he designed for the daily recording of meteorological data, to be presented at the Paris Universal Exposition; here the instrument obtained the attribution of the Grand Prix, while the same Secchi received the Legion of Honor from the emperor of France Napoleon III and the Order of the Rose by the emperor of Brazil Pedro II: his scientific career reached the climax .

With the capture of Rome in 1870, a period of great difficulty began for Secchi. A world-renowned scientist, he became an uncomfortable figure in the context of the then conflicting relations between the Italian Government and the Papal State.

Substituting the papal authority, the unitary government, under pressure from the international scientific community, left Secchi to the direction of the Osservatorio del Collegio Romano, accepting the conditions he had established in agreement with his superiors. The Government also offered him the university chair of Physical Astronomy at the University La Sapienza, which Secchi initially accepted but which he was then forced to renounce for exclusively political reasons, related to the freedom of teaching of Jesuits in schools. In that same year, Secchi published the first edition of the famous treatise Le Soleil (1870), one of the most important solar astronomy texts of the nineteenth century.

But the situation precipitated in 1873, with the confiscation of ecclesiastical assets and the consequent passage of the Roman College under the dependencies of the Italian government. Secchi tried by every legal means to defend the Observatory, in which he had invested money and energy, asking that it be recognized as a Pontifical Observatory and therefore protected by the law on Guarantigie. In the first instance he obtained that the premises of the Observatory were isolated from the rest of the building, maintaining access for himself and his collaborators.

In 1875 he participated in the Congress of Italian Scientists in Palermo and was invited on that occasion to be part of the government commission established to plan the national meteorological service. This proposed to the Government the establishment of a Central Office and a Directive Council for Meteorology for the coordination of national meteorological services; the Council was established in November 1876 and in March 1877 Secchi was elected President.

His health, meanwhile, always rather shaky, was deteriorating; he had to progressively abandon the research activity, devoting himself more and more to the drafting of works and treaties. In 1875 he published the first volume of the second edition of Le Soleil and in 1877 he followed the second volume and the treatise Le stelle. Essay of Astronomy Sidereal. The publication of his Lessons of Earth Physics was prepared (later published posthumously in 1879) when, in August 1877, the first symptoms of a stomach cancer were manifested, which within a few months was right of its strength. On the advice of the doctors, in an attempt to find benefit from his suffering, at the end of November of that year he went to the Villa s. Girolamo in Fiesole. However, he did not obtain any improvement and, feeling his health deteriorate, he returned to the Roman College at the end of December. He endured with dignity and resignation the last difficult months of illness, extinguishing on February 26, 1878, at the age of 59.

The convictions on the relationship between science and faith

Angelo Secchi represents the meeting point between the passionate scientist and the man of faith convinced and open to dialogue: in his writings never emerge tips of fanaticism or clericalism. What is most striking in him is fidelity to the Church and the great love of truth, tenaciously pursued with the means of science and with the principles of faith. Lived in an age not easy for the relations between State and Church, as well as between science and faith, he gave a singular testimony of solid coherence of lived faith and intelligent and profound scientist, from innovative and, in some way, foundational solutions for the astronomy of his time. He was able to sustain many difficulties, misunderstandings and bitterness, but he always did so with a great sense of professionalism and Christian charity.

| data /date | 28.06.2018 |

| n. catalogo / n. catalog | Michel 4051 – YT 3812 – UN. 3894 |

| dentellatura/Serration | 11 |

| stampa/printing | fustellatura – rotocalco |

| tipo di carta/paper type | bianca patinata neutra |

| stampato | I.P.Z.S. Roma |

| fogli/sheet | 28 |

| dimensioni/dimensions | 48 x 40 mm |

| disegnatore /designer | C. Bruscaglia |

| tiratura | 400.000 |

I often visit your site and have noticed that you don’t update it

often. More frequent updates will give your website higher rank & authority in google.

I know that writing content takes a lot of time, but you can always help yourself with miftolo’s tools which will shorten the time

of creating an article to a couple of seconds.

Thanks for your advice! I will try to apply them even if, by itself it is very difficult to insert all my products. Follow me again and advertise. THANK YOU